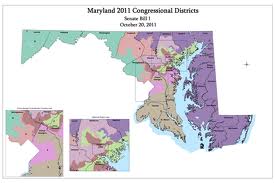

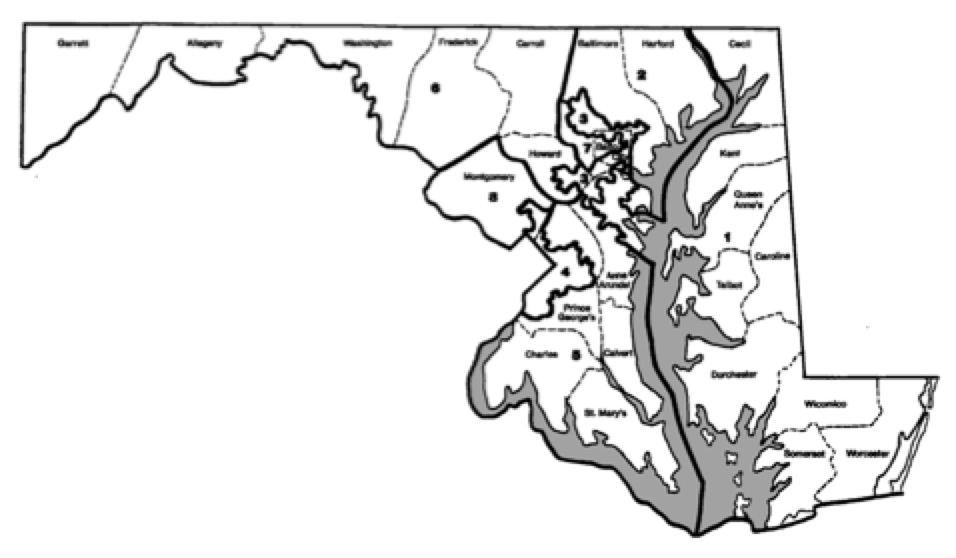

The General Assembly is moving forward with the redistricting plan recommended by the Legislative Redistricting Advisory Commission.

Redistricting in America emphasizes population equality very heavily. Congressional plans have been overturned by federal courts for unjustified deviations from population equality of as little of 20 people. Many states adopt plans in which the most populous district has only one more person than the least populous district to insulate them from challenges on these grounds.

The federal courts have usually given state legislative plans more wiggle room, though they have not always deferred to jurisdictions that meet a standard of having deviations less than 5 percent above or below the ideal population, or 10 percent total.

The Maryland plan meets the 10 percent standard but the cumulative impact of variations in legislative district size across multiple districts within some jurisdictions may raise eyebrows. Some counties are noticeably over or underrepresented compared to others.

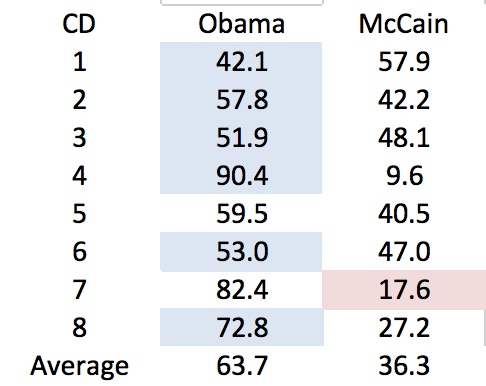

The table at the top of this post shows the legislative district (LD) entitlement of various jurisdictions based on population. Each LD elects one senator and three delegates with some divided into two or three subdistricts for purposes of delegate elections.

The table further reveals the how many LDs were allocated to jurisdictions along with the difference from their entitlement based on population. The final column shows the same information in terms of the number of delegates, which is just three times larger than for the entire LD. Where a proposed subdistrict or district spans a county line, I allotted the representation from the district based on population.

Most areas are quite close to their population entitlement, but a few areas stand out as winners and losers. Together Baltimore City and County have nearly an entire delegate more than they are entitled to based on population. Baltimore City has 55% of a delegate more than entitled to based on population while neighboring Baltimore County has 44% more.

Meanwhile, Prince George’s has 70% less of a delegate than it merits based on population. Prince George’s together with the three southern Maryland counties of Charles, Calvert and St. Mary’s together merit an additional delegate based on population. The Eastern Shore as a whole is also down 28% of a delegate.

Perhaps it is not coincidental that House Speaker Adrienne Jones lives in Baltimore County and the Senate President Bill Ferguson lives in Baltimore City. It is also part of a history of Democrats trying to protect Baltimore City from its long-term population decline.

The City of Baltimore had 11 LDs in 1974 but will be down to 4 2/3 if this plan goes into effect for 2022. Past efforts to preserve City influence by extending existing City districts into Baltimore County led to the Maryland Court of Appeals overturning the 2001 map for General Assembly districts.