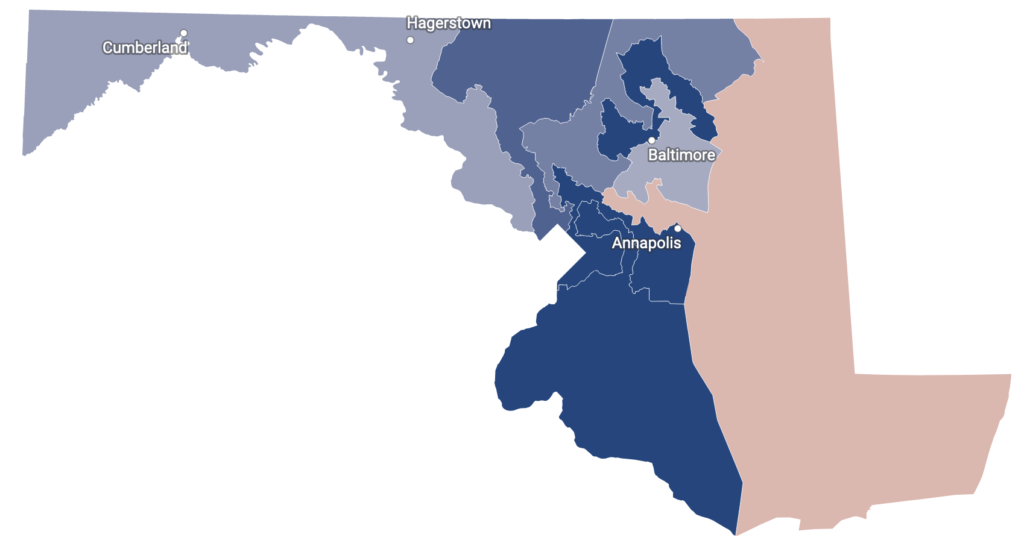

This post is a collection of the new councilmanic district maps from around Maryland. It is an updated version of one of the most popular posts on Seventh State with the 2010s maps. I have done my best to make sure that they are the new rather the old districts. I have been unable to locate the new Baltimore City, Garrett County, and Talbot County Council maps.

If you know where I can find them or if any of the maps here are incorrect, please let me know. It’s often hard to be completely sure which proposed maps have been adopted. Additionally, some of the new maps are exceedingly similar to the old ones. My hope is to put up a complete and corrected post in the future.

The maps here are organized by the type of electoral system used by the county starting with (1) elected at-large with district residency requirements followed by (2) elected entirely from districts, and (3) elected by a mixture of districts and at-large. Counties are listed alphabetically within each category.

Allegany, Caroline, Kent and Washington Counties elect their entire county commissions at large.

ALL ELECTED AT-LARGE WITH A RESIDENCY REQUIREMENT

Calvert County: Five commissioners with two with no residency requirement and three from districts.

Charles County: Five commissioners. There is no residency requirement for the commission president with four additional commissioners elected from districts.

Cecil County: Five commissioners with staggered terms.

Any changes from the previous map appear very small.

Garrett: Three commissioners. No map available.

Queen Anne’s: Five commissioners. There is no residency requirement for one commissioner with four additional commissioners elected from districts.

St. Mary’s: Five commissioners. There is no residency requirement for the commission president with four additional commissioners elected from districts.

Talbot: Five councilmembers. No map available.

ALL ELECTED FROM DISTRICTS

Anne Arundel: Seven councilmembers.

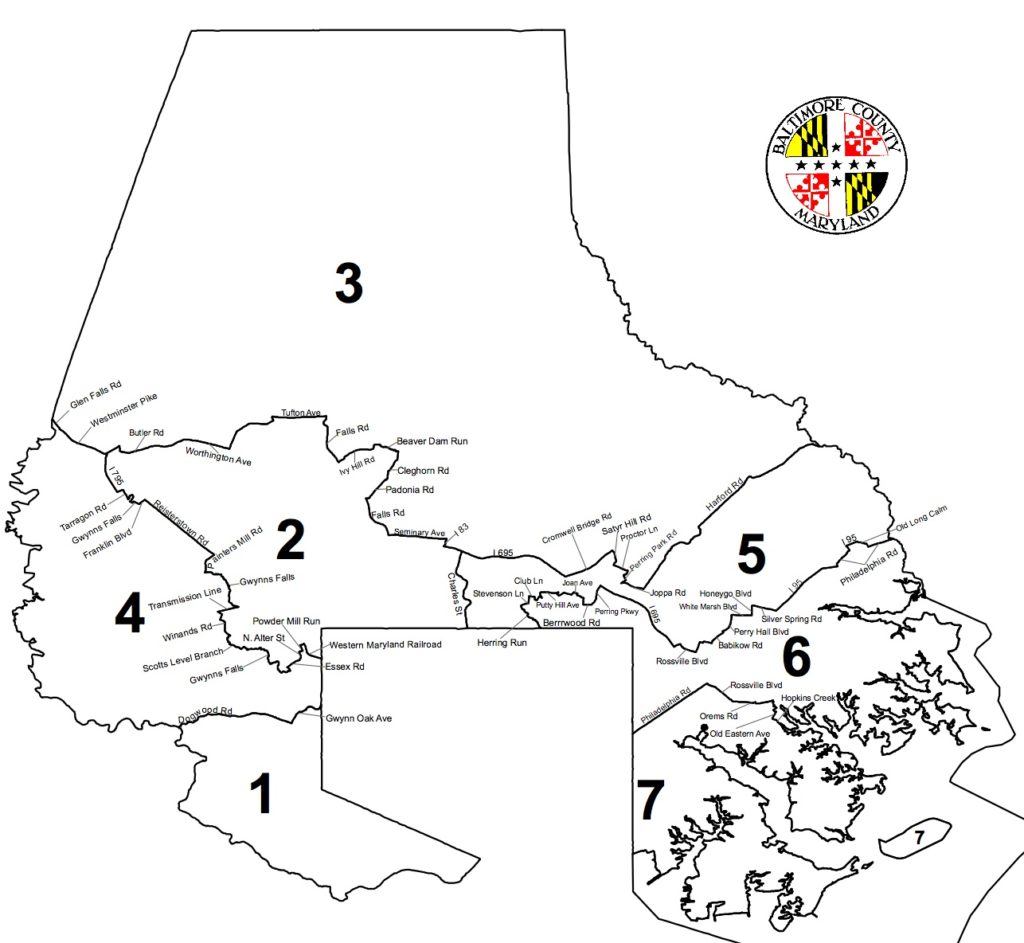

Baltimore County: Seven councilmembers.

This map was the subject of voting rights litigation over the county’s failure to create a second majority-black district.

Carroll County: five commissioners.

Dorchester County: five councilmembers.

The changes from the previous map, if any, appear small.

Howard County: five councilmembers.

Prince George’s: nine councilmembers.

Somerset County: five commissioners.

Worcester County: seven commissioners.

Any changes appear very small. Please let me know if this is not the current map for the county.

MIXED

Baltimore City: 15 councilmembers with 14 elected from districts and the council president at-large. No map available.

Frederick County: five councilmembers elected from districts and two elected at-large.

Harford County: six councilmembers elected from districts and the council president elected at-large.

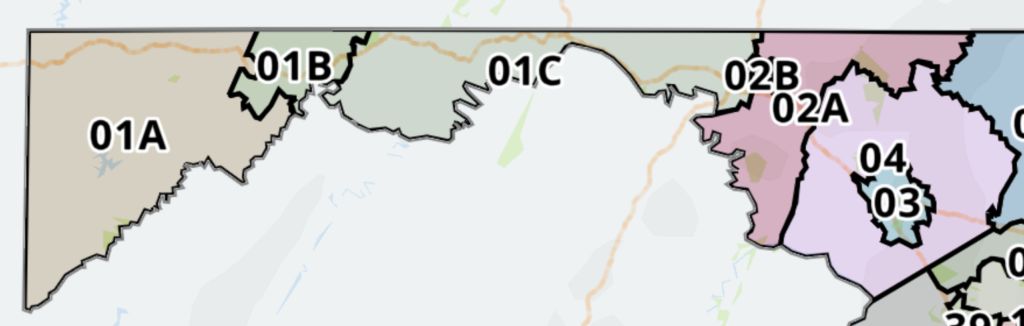

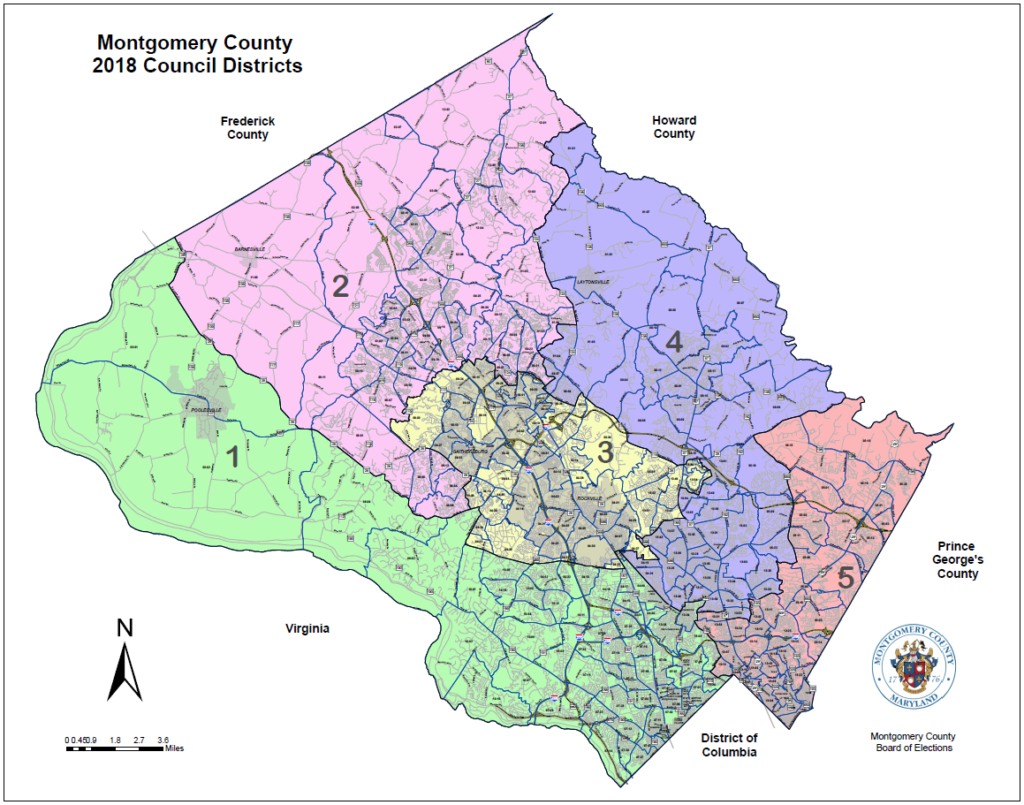

Montgomery County: seven councilmembers elected from districts and four elected at-large.

This map adds two new districts over the previous version, increasing the size of the council from nine to eleven.

Wicomico County: five councilmembers elected from districts and two elected at-large.