By Adam Pagnucco.

Thanks to Council Member Nancy Floreen for writing about MCPS funding in recent years in response to my blog post. First, a note of appreciation. While we may disagree about MCPS, we agree wholeheartedly on the issue of economic growth, which is the anchor for the county budget. The political winds on growth shift back and forth in county politics over the decades, but Floreen has consistently pushed an economic development agenda. She was for jobs before jobs were cool! All the things the county has done right in economic development – and there have been a few of them – have Floreen’s fingerprints all over them. It’s one reason why your author admires her and is sad to see her leave the County Council.

Let’s begin with areas of agreement. First, Floreen is absolutely right about the terrible days of the Great Recession. The county had not faced anything like it since the 1930s. Everything had to go on the table in those days – spending cuts, layoffs, furloughs, broken collective bargaining agreements and an energy tax hike – because the alternative was default. Floreen was Council President in 2010, the worst year of the recession. She, the County Executive and her colleagues saved the county from fiscal disaster. That achievement should not be forgotten.

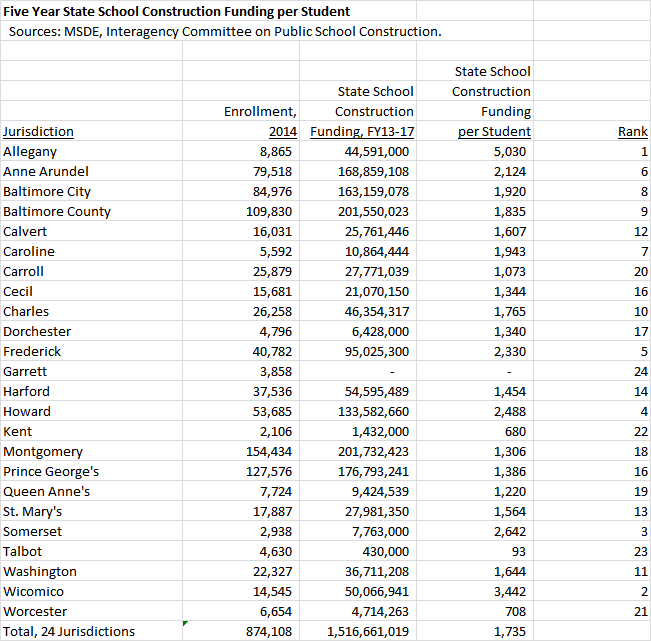

Second, Floreen mentions the state’s teacher pension shift as a stress point on county finances. Again, she’s absolutely right. For many years, the state’s payment of teacher pension benefits was the one state program that disproportionately benefited Montgomery County. That’s because our high cost of living as well as our prioritization of schools leads us to pay higher teacher salaries than the rest of the state, which results in higher pensions. In 2010, nearly all of MoCo’s state legislators running for election promised not to shift pension costs to the counties. But in 2012, Governor Martin O’Malley pushed a plan to do exactly that and most of our state legislators voted for it. The result is that Montgomery County pays roughly $60 million a year for teacher pensions now, more than any jurisdiction in the state. Compare that to the size of last year’s property tax hike, which was $140 million a year. No matter what is said about the county, the state should not be let off the hook.

Now to the areas of disagreement. It’s interesting that Floreen says our blog post is misleading but does not actually refute any of the data on which we rely. She simply picks other data and disagrees with our characterizations. We are sympathetic to her problem: it’s hard to refute data that happens to be true! One thing she contests is our choice of FY10 as a base year for comparison. We picked FY10 because it was the peak year of overall county spending before the Great Recession fully kicked in. So comparing FY10 to FY16, the year before the tax hike, is valid because it’s a peak-to-peak comparison that includes both the cuts to departments in the early part of the period as well as the restoration that occurred afterwards.

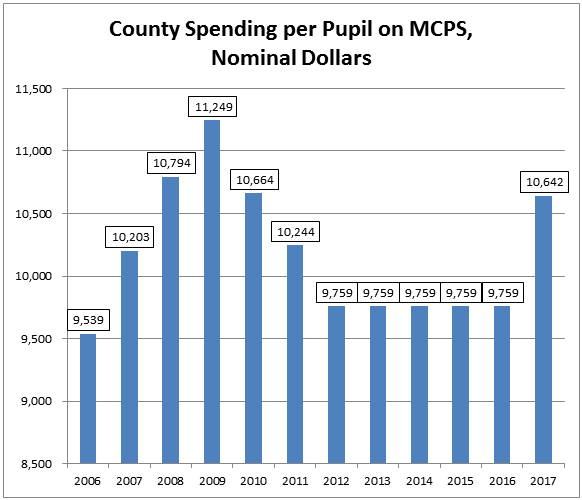

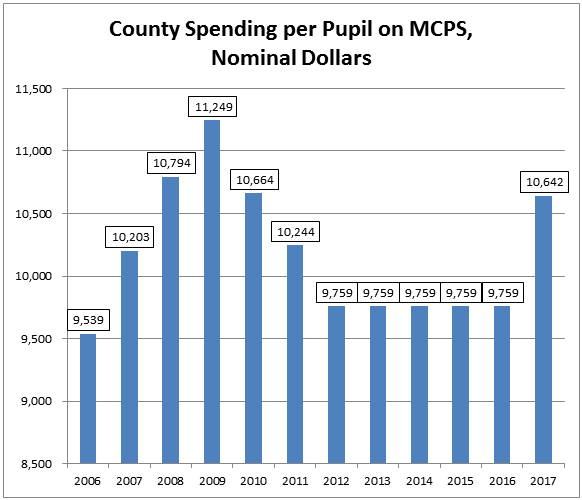

She also disagrees repeatedly with our referring to MCPS as going through austerity. Our basis for doing so was the county’s local dollar spending per pupil, which comes from county budget documents and was not contested by Floreen. In nominal terms, here is the county’s local spending per pupil from FY06 through FY17.

The data shows that the county cut its local per pupil contribution to MCPS for three straight years and froze it for four straight years. This period greatly exceeds the length of the Great Recession. The local per pupil contribution went up after last year’s property tax increase.

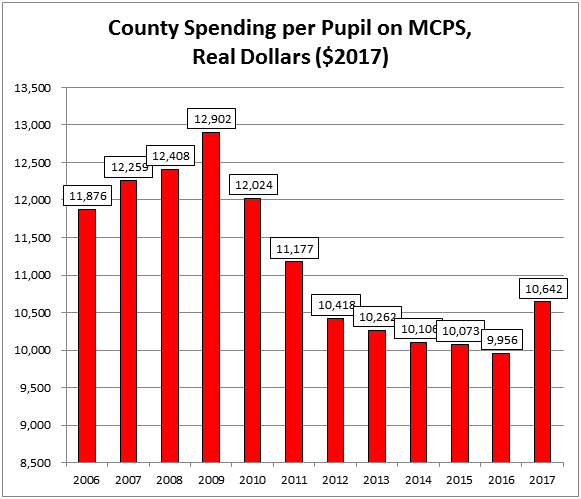

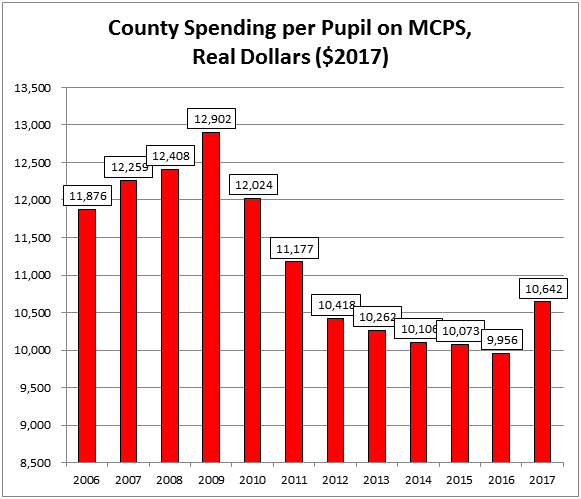

Last year’s per pupil bump looks significant, but here is the same data adjusted by the Washington-Baltimore CPI and presented in real terms using 2017 dollars. (We estimated 2017 inflation at 2.02%, the average rate of the preceding years in the chart.) Clearly, even with the tax hike, the county’s local-dollar commitment to schools is not what it once was. And the CPI underestimates major cost drivers for the schools, such as the costs of serving rising numbers of students who live in poverty and need language services.

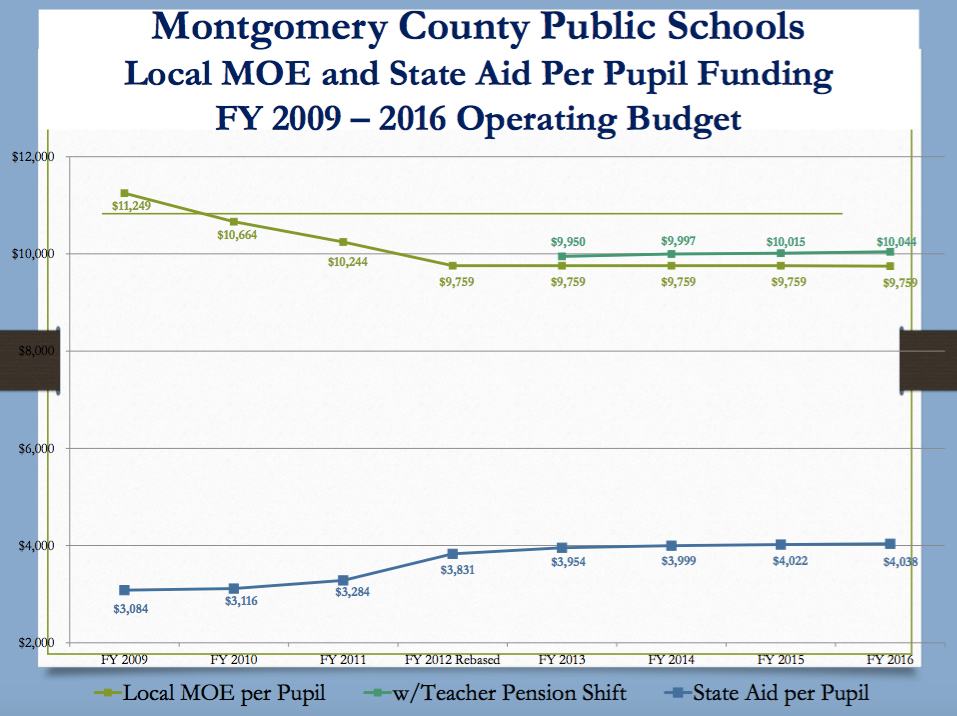

Floreen then talks about the county departments that were cut during the recession. She’s right: they were cut. But after the recession ended, most of them were restored to levels exceeding what they were before the recession. Meanwhile, county dollars for MCPS were cut by $33 million between FY10 and FY16. Floreen doesn’t deny that, but she notes that local dollars aren’t the only source for MCPS’s budget. The schools get plenty of state money too. Floreen says this:

What really matters is the total MCPS budget, not the State share versus the local share. The higher State spending for MCPS in recent years reflects that the State’s funding formulas, at long last, are starting to recognize our students’ actual needs, as shown in our higher ESOL and FARMS populations. The State aid increases, which were long overdue, enabled us to provide continued strong support for MCPS during the Great Recession without further decimating every other function of government. Why is that not a good thing?

Floreen is conceding a central point of our original post which is reinforced in the per pupil data above: the county depended on state aid to keep MCPS afloat while it restricted its own contributions to the school system. Meanwhile, MCPS enrollment grew from 140,500 to 156,514 between FY10 and FY16, an 11% increase. The Great Recession by itself can’t be cited as a justification for restricting county dollars for schools because the restrictions continued long after the trough of the recession had passed. Indeed, fifteen other counties increased their local per pupil contributions after the recession ended, including nine controlled by Republicans. The message here is, “The state was paying for our schools so we didn’t have to increase county per pupil spending on them.” Is that “continued strong support for MCPS” as claimed above? Is it satisfactory for parents and voters? Let the readers decide.

Finally, Floreen repeats her longstanding point that last year’s 9% property tax hike was intended to support MCPS. That’s true: MCPS did get a big share of that money. But so did the rest of the government. Last year, we laid out how the county could have cut the tax hike in half, still given MCPS all the money requested in the County Executive’s budget and done it without spending cuts to other agencies. County Executive Ike Leggett, who originally proposed the tax hike, asked the council to cut the rate increase in half after the General Assembly passed a law easing the county’s liability from a U.S. Supreme Court decision on income taxes. But the council chose to keep every penny of the original tax hike and spread it across every agency instead. That’s not an Education First budget – it’s an Everything First budget. The result of the tax hike was a tremendous boost for the 40-point triumph of term limits at the ballot box. Even the council’s own spokesman at the time now says the tax hike was unnecessary and is vowing to stop another one if he is elected to Floreen’s open seat.

Look folks. We get this is tough medicine. We understand that elected officials don’t like to be criticized, especially around election time. And we understand that Nancy Floreen, a Council Member we respect, would like to go out on top. But it’s important to understand the past to prepare for the future. The schools need small, steady increases in per pupil funding to deal with their challenges. There can no longer be wild swings between extended periods of per pupil cuts and freezes followed by huge tax hikes intended to undo the effects of those cuts and freezes. To fund MCPS fairly without raising taxes, the county will have to restrain the overall growth of the rest of the budget to pay for it. There cannot be any more Everything First budgets. With four Council Members leaving and the Executive race wide open, it will be up to the next generation of county officials to chart a better way forward.