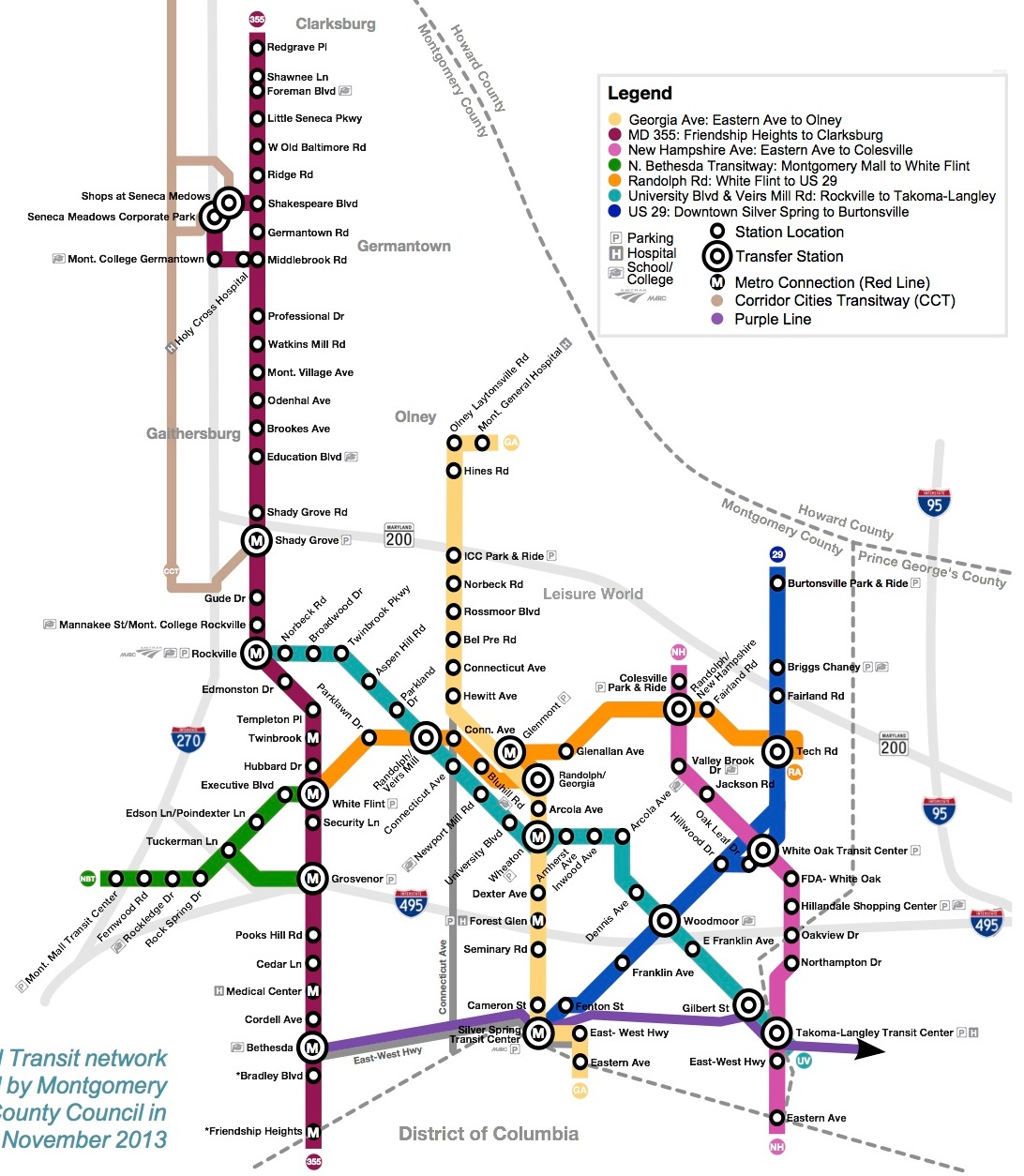

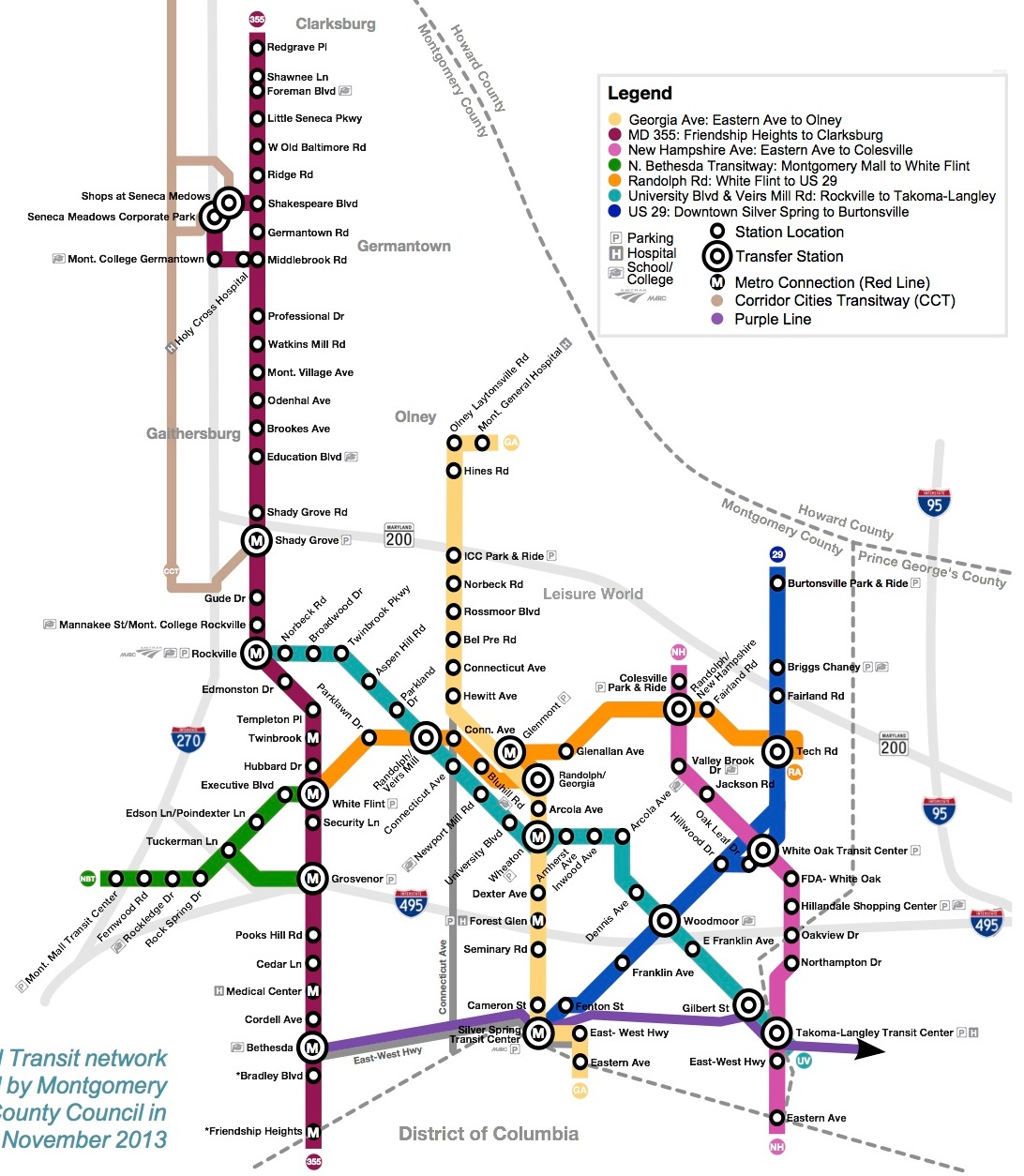

Proposed Rapid Transit System Map

Montgomery County has adopted plans for a bus rapid transit system (RTS) of nearly 96 miles. This system includes not only the long planned Corridor Cities Transitway (CCT) of 15 miles but a separately planned system of nearly 81 miles.

Proposed and pushed relentlessly by at-large Montgomery County Councilmember Marc Elrich, the plan to add 81 miles is the most ambitious effort to expand public transit in the area since Metro. While other jurisdictions, including DC and Alexandria, are ahead of Montgomery in moving ahead with RTS, Montgomery’s is the most extensive network.

The above schematic map shows the proposed routes as well as the planned light-rail Purple Line and CCT. The map produced by Communities for Transit, an RTS advocacy group, uses the familiar Metro system design, which makes it look attractive but also misleadingly suggests that RTS is heavy rail like Metro. It’s not. Repeat: map looks like Metro; system is not Metro.

On the other hand, I understand the drive by proponents to avoid the word “bus.” In the DC area, people associate the buses with Metrobuses–the slowest still moving form of transportation ever invented. Drivers perceive buses as barely moving hulks to avoid and to pass. Though RTS is not heavy rail, it is also definitely not Metrobus.

RTS buses move much faster and are much nicer, more analogous to light or heavy rail cars. These buses are also designed to approach platforms at level–again like Metro or light rail–so there is no climbing up or down.

Greater speed than conventional buses is achieved because RTS buses usually travel in their own dedicated lanes. There can be two lanes on either side of the street along the curb or two in the median. Alternatively, in tighter areas, there may just be one lane that switches direction. Buses traveling in the direction of heavy traffic use the dedicated lane while buses going in the other direction travel with regular traffic.

In some areas with little room, the buses may have to travel in regular traffic in both directions. However, even in these areas, RTS buses can go faster than regular buses because they communicate to hold the traffic lights so that they can make the lights if they are close to the light but it’s about to change.

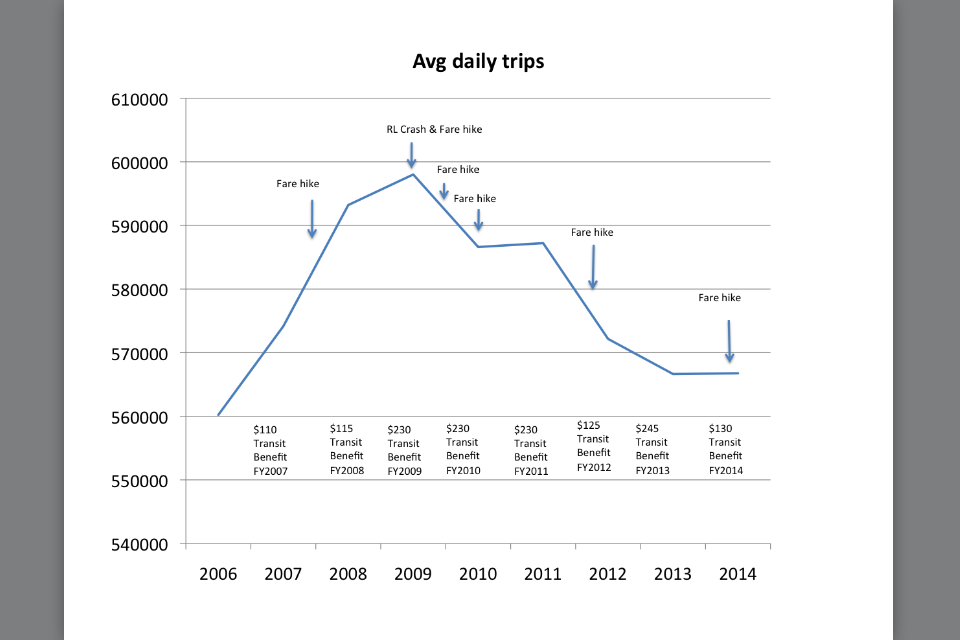

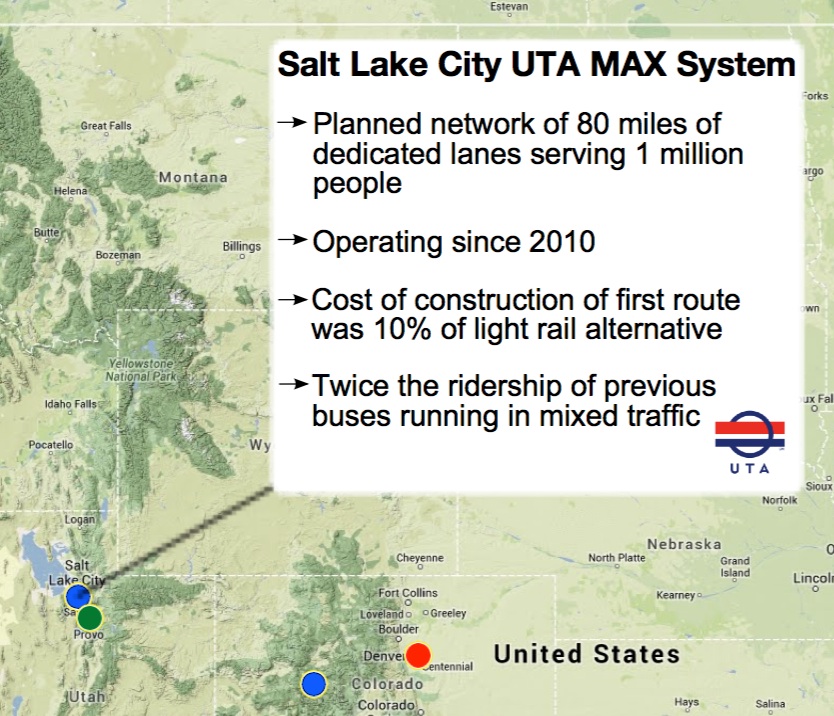

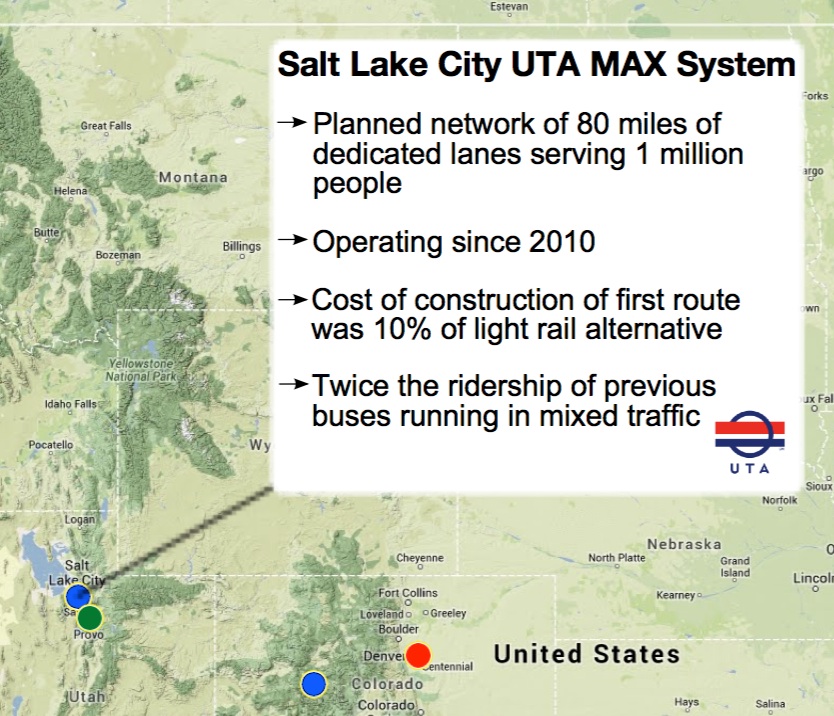

People often wonder why we don’t just expand Metro, like the delayed Silver Line in Virginia, or build light rail, like the planned Purple Line, instead. They reason is cost. RTS is far cheaper than either of these methods. This item from the Communities for Transit presentation caught my eye:

In Salt Lake City, light rail would have been ten times as expensive as the RTS alternative. The price difference means that Montgomery can get far more bang for the buck with RTS. Indeed, the CCT was originally planned as a light rail but is now expected to be a bus rapid transit system, so that it is financially feasible.

The low cost is critical because, even with the Governor’s successful drive to take measures to expand Maryland’s transportation fund, there is not nearly enough money for all of the State’s transportation priorities from roads and Baltimore’s Red Line to MARC and Metro (those elevators. . . ).

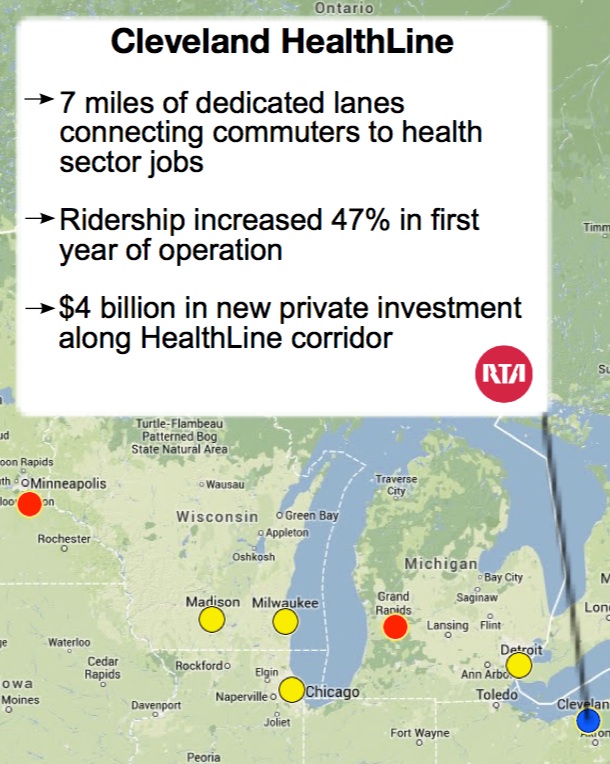

One of the most appealing aspects of RTS is the potential, and it remains just potential, to help weaken the battles between civic groups and developers. Developers want greater density while civics worry about the impact on infrastructure, especially the increased traffic.

The Montgomery RTS plan allows more growth to occur in the context of a system designed to address heightened traffic and also to spread development, along with its benefits and problems, around a much larger area rather than one or two nodes. It recognizes that Montgomery remains a spread out suburban area even as we develop multiple new urban centers.

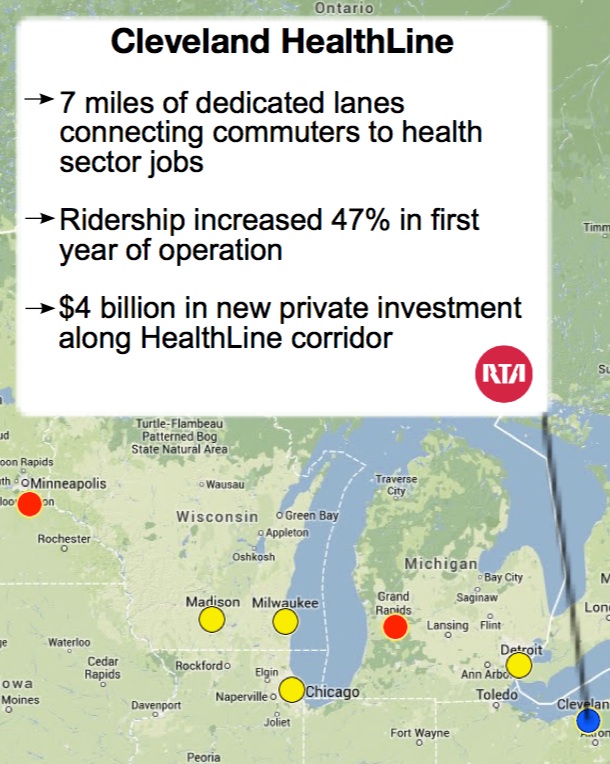

According to Communities for Transit, RTS does produce additional investment:

And growth needs to occur to provide jobs and income, as well as to pay the taxes to regenerate our aging infrastructure and expand it. The key is to invest the public transit money wisely.

Just More Media Hysteria, So Chillax

Just More Media Hysteria, So Chillax