By Council Member Nancy Floreen.

Adam Pagnucco’s recent post on the County Council’s budgeting work made an astoundingly misleading claim: “The County imposed seven years of austerity on MCPS [in FY10-16] while lavishing double-digit increases on nearly every other function of government.” While I ordinarily ignore this kind of online misrepresentation of Council activity, this goes too far over the top to let pass.

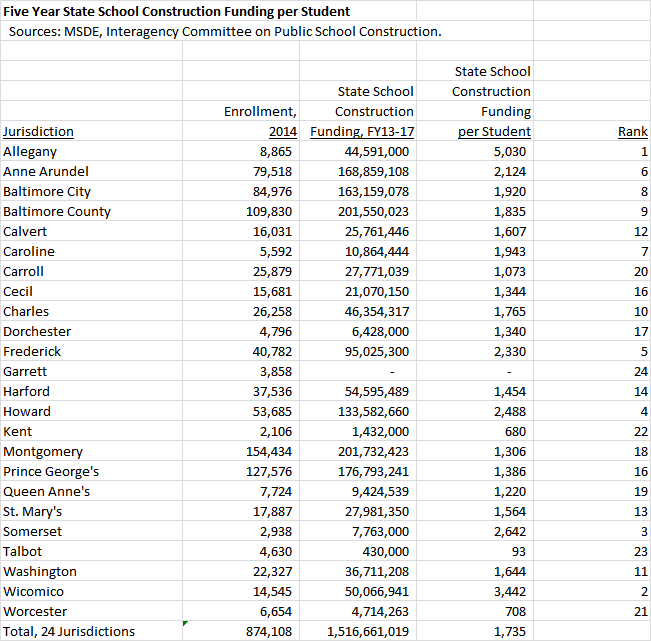

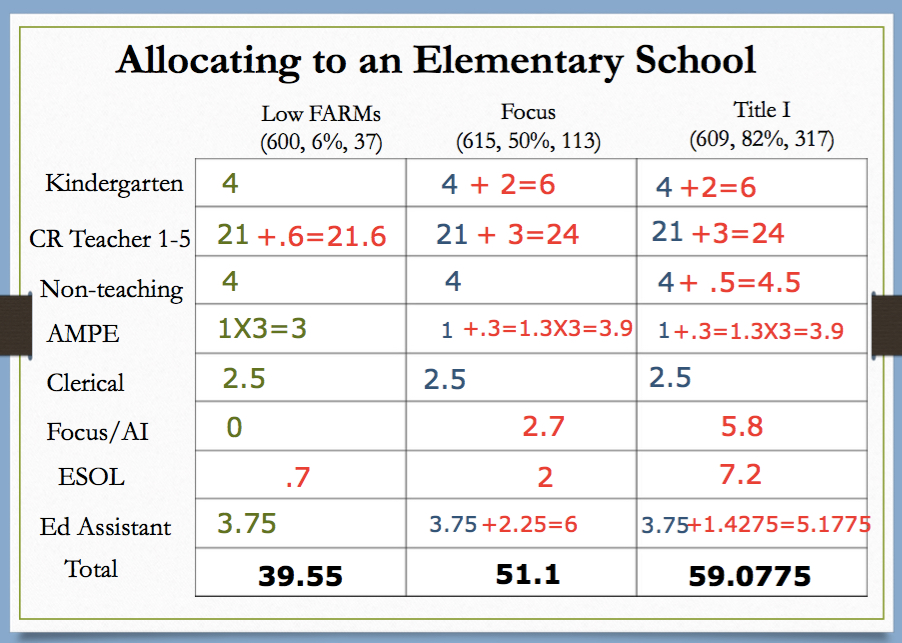

As Council President in 2016, I plead guilty to leading the charge for two tax hikes to support MCPS. The FY17 property tax hike enabled us to reduce class size and focus on the achievement gap; we exceeded the State-required Maintenance of Effort level (MOE) for the MCPS operating budget by $89 million. The recordation tax hike enabled us to fund key school construction projects that would otherwise have languished. We did this in a historic partnership with the Board of Education, which agreed to channel more of its funds to the classroom, and, bravely, less to employee compensation.

Were the preceding seven years really a period of “austerity” for MCPS and “lavish” times for others? Consider the facts.

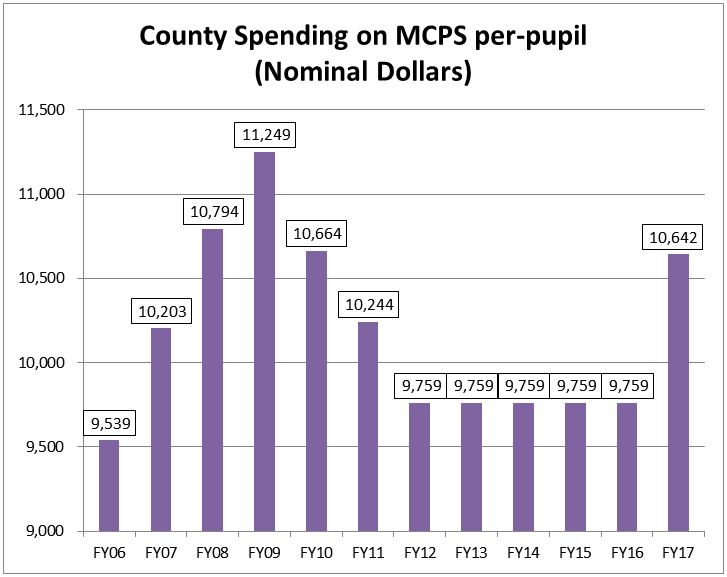

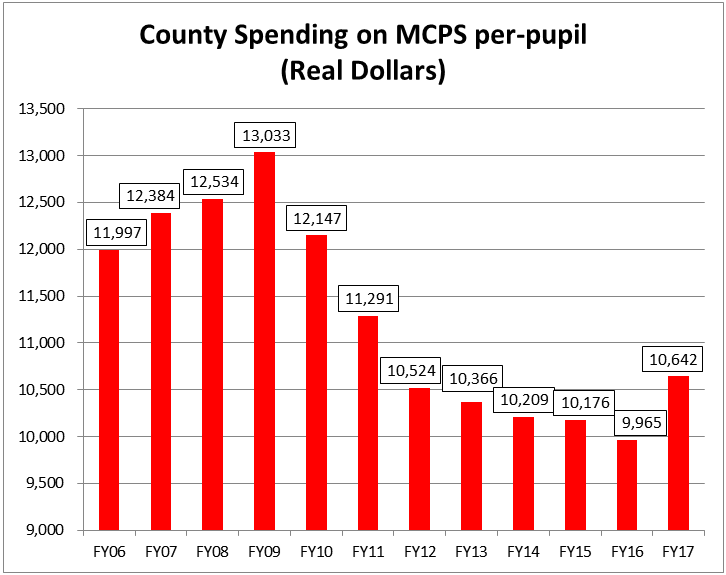

1. The choice of base years matters. FY10 was an anomaly. From FY01-09, we had funded MCPS at a total of $576 million ABOVE the MOE level, thus creating a much higher required spending base. But no good deed goes unpunished. When revenues sank like a stone during the Great Recession, this higher base became an impossible burden, even after we approved a property tax increase in FY09.

2. During the worst years of the recession, FY09-12, only two agencies – MCPS and Montgomery College – saw increased funding. To be sure, the increases were small (1.8 and 3.2 percent, respectively) and relied on higher State aid. But during this same period, vital County functions like Police, Fire and Rescue, and HHS were down 3.4, 5.0, and 14.7 percent, respectively. Recreation was down 23.5 percent, and Libraries was down 29.2 percent. These deep cuts were without precedent. The new spending base we were forced to create was so low that any later increase seemed disproportionately large. We consistently prioritized funding for MCPS and the College during this period. As the Rolling Stones would say, they didn’t get what they wanted, but they got what they needed. This we could not do for the rest of County government. I was Council President in that awful time. There were furloughs for all County employees, including first responders. MCPS furloughed no one.

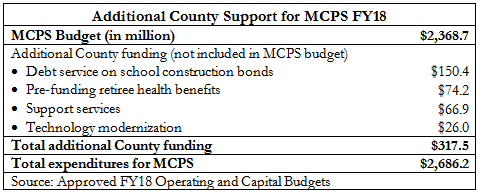

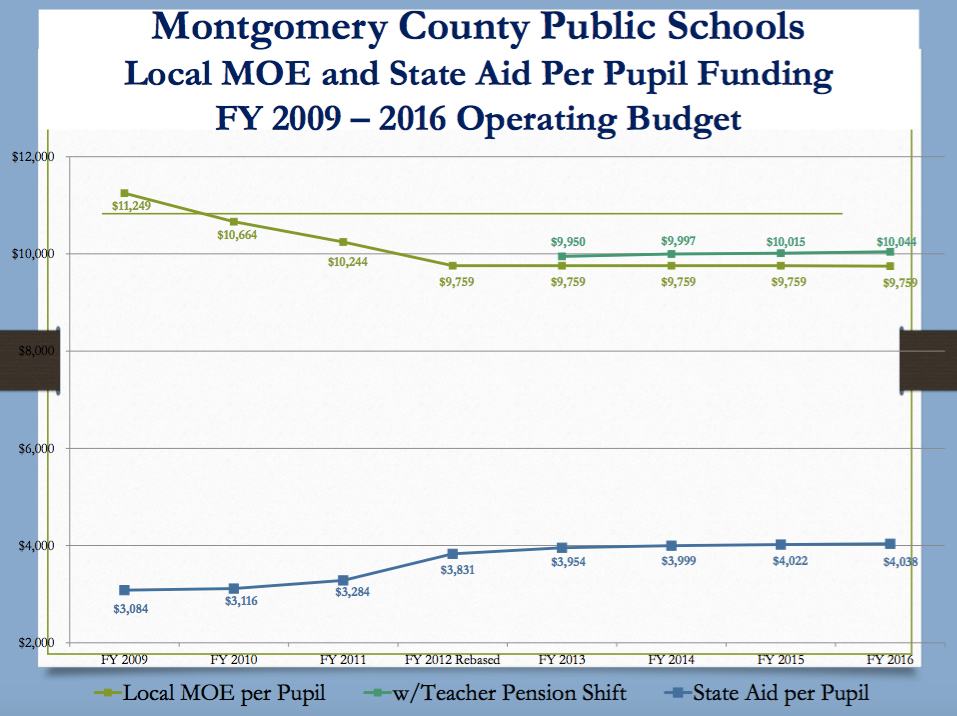

3. The “austerity” claim fails to account for massive additional County funding for MCPS that is not included in the MCPS budget or in MOE. So, for example, in FY18, we approved total expenditures for MCPS that include $2.37 billion for the MCPS operating budget PLUS $317.5 million more in the County budget. This pays for debt service on school construction bonds, pre-funding MCPS retiree health benefits, support services ranging from Linkages to Learning to crossing guards, and MCPS technology modernization. In FY13-16 alone, this additional County support totaled $1.08 billion. These dollars are not technically included in the MCPS budget, but they should be. To put the FY18 additional County support in perspective, this amount is larger than the total FY18 budget for Police, Fire and Rescue, or HHS. Again, this massive support for MCPS is all ABOVE the MOE level. And not counted.

4. Is the flip side of this alleged “austerity” for MCPS in FY10-16 really “lavishing double-digit increases on nearly every other function of government”? Tell that to one of our most important and beloved departments, Public Libraries. The libraries provide our one million-plus residents of all ages (including students from MCPS) with an ever-growing wealth of materials and technology. But the department’s budget of $40.3 million in FY09 did not reach that level again until FY16, seven years later, even in nominal dollars. The FY18 level, $42.7 million, is barely equal to FY09 in real dollars. “Lavish” indeed!

5. One key fact is that 90 percent of the MCPS budget is for the salaries and benefits of active and retired employees. MCPS’ benefits cost much more than the County’s. If MCPS’ employee share of health insurance costs was the same as the County’s, the savings would be $24 million. Add to this the fact we alone in the State fund a supplement to MCPS employees’ State pension benefit. This alone cost $25.3 million last year. The regular pension cost in FY18 is another $71.8 million, plus $56.8 million more for the State’s shift of teacher pension costs. We also pick up the tab for pre-funding MCPS retiree health benefits (paid from the County budget, not the MCPS budget). This set us back $74.2 million in FY18 and is now projected to cost $547.8 million in FY18-23. Is that what you call “austerity”?

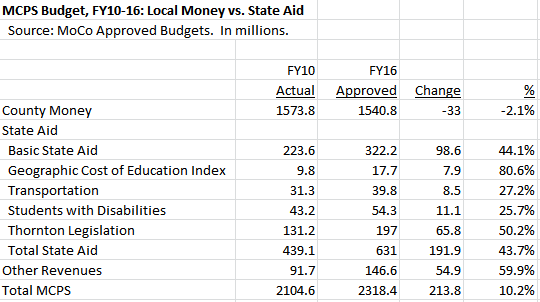

6. What really matters is the total MCPS budget, not the State share versus the local share. The higher State spending for MCPS in recent years reflects that the State’s funding formulas, at long last, are starting to recognize our students’ actual needs, as shown in our higher ESOL and FARMS populations. The State aid increases, which were long overdue, enabled us to provide continued strong support for MCPS during the Great Recession without further decimating every other function of government. Why is that not a good thing?

7. In fact, a more complete and accurate comparison of FY10-16 tax supported operating budgets by agency shows that MCPS received a 12.9 percent funding increase compared to 13.0 percent for Montgomery County Government, 15.9 percent for Montgomery College, and 8.3 percent for Park and Planning. In addition, a significant portion of the FY10-16 increase of 803.9 percent in pre-funding retiree health benefits and 41.5 percent in debt service benefited MCPS!

As we go into an election year of hyperbole and catchy phrases, know that the Council, on which I have been so privileged to serve, is committed to thoughtful fact and policy based budgets, responsive to ALL our residents’ needs. We are also constantly mindful of the burden that our decisions place on our residents’ pocketbooks. MCPS will always need more support. Has it been singled out for unfair treatment – “austerity” for MCPS and “lavish” increases for everyone else? The facts say otherwise.

Nancy Floreen has served on the Montgomery County Council since 2002. She was Council President in 2010, during the Great Recession, and again in 2016.