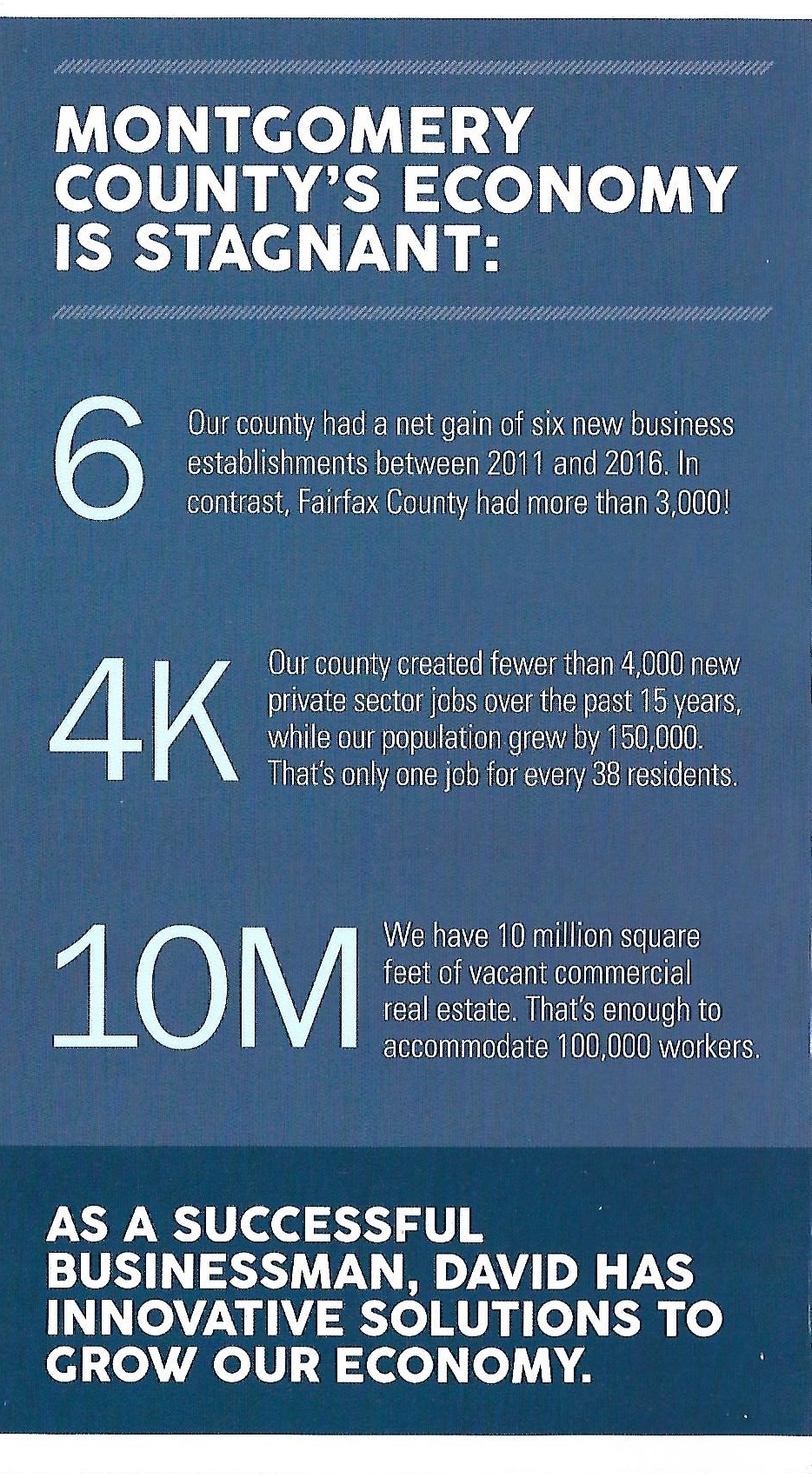

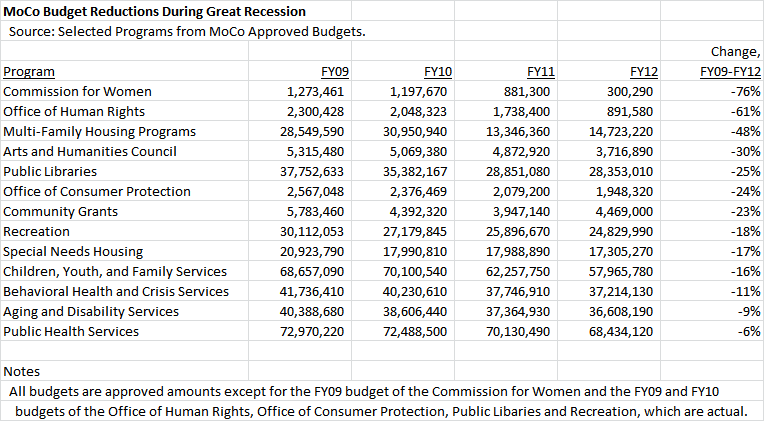

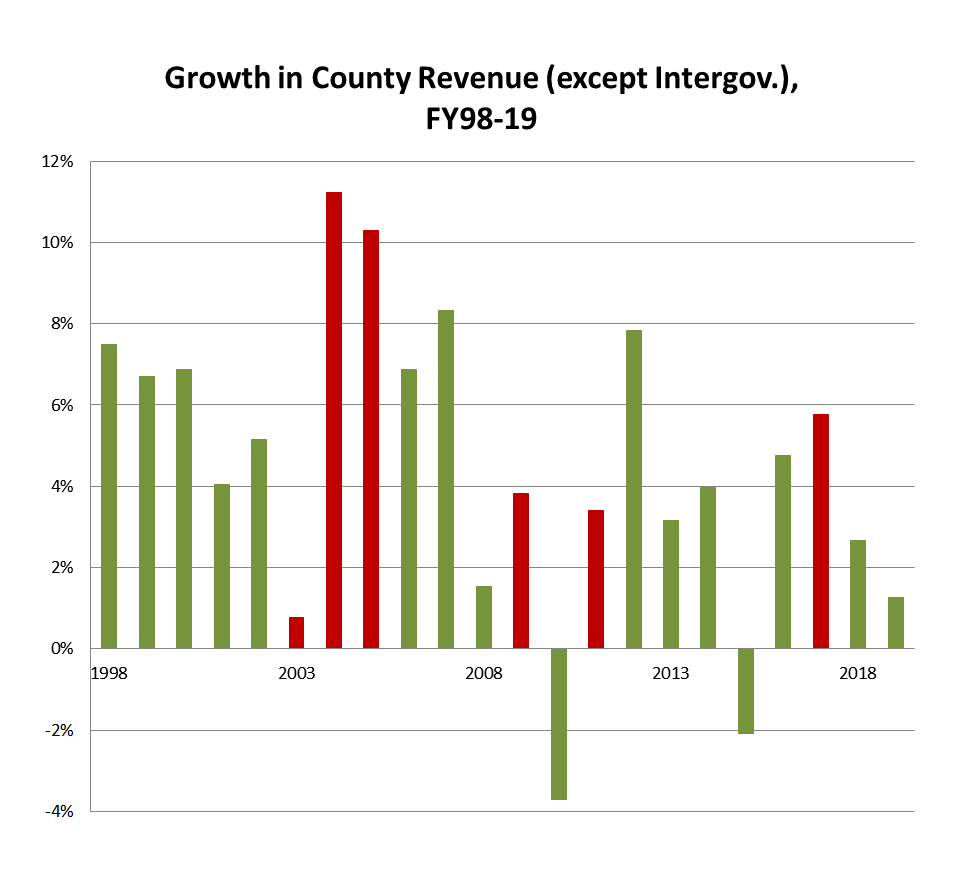

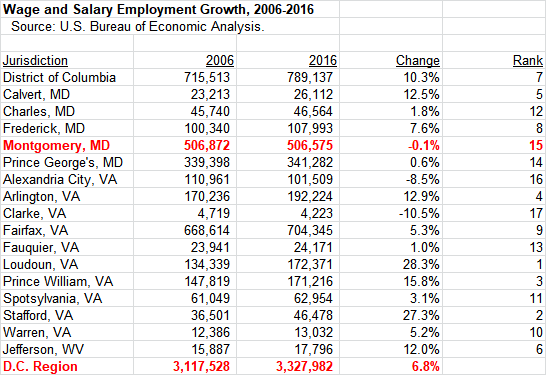

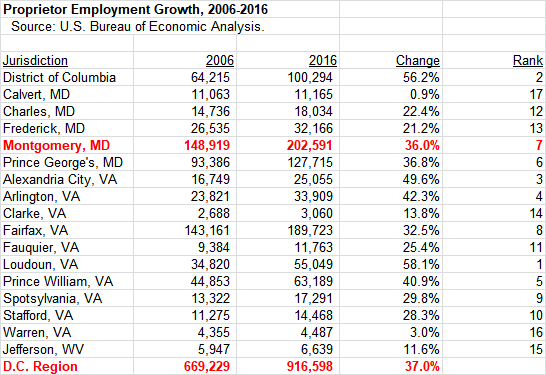

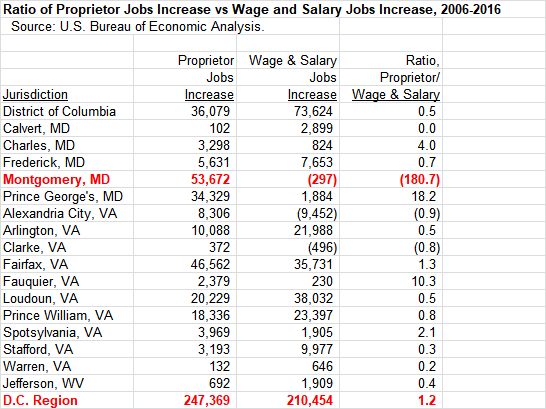

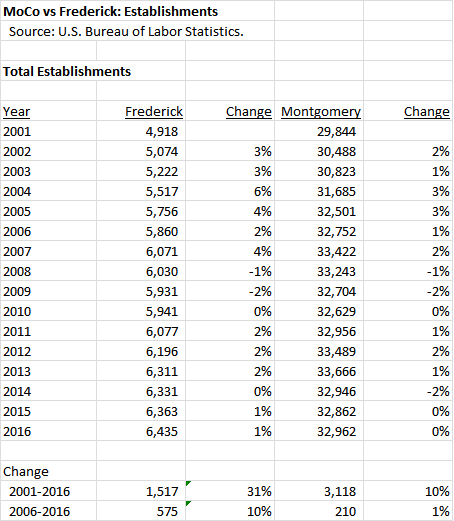

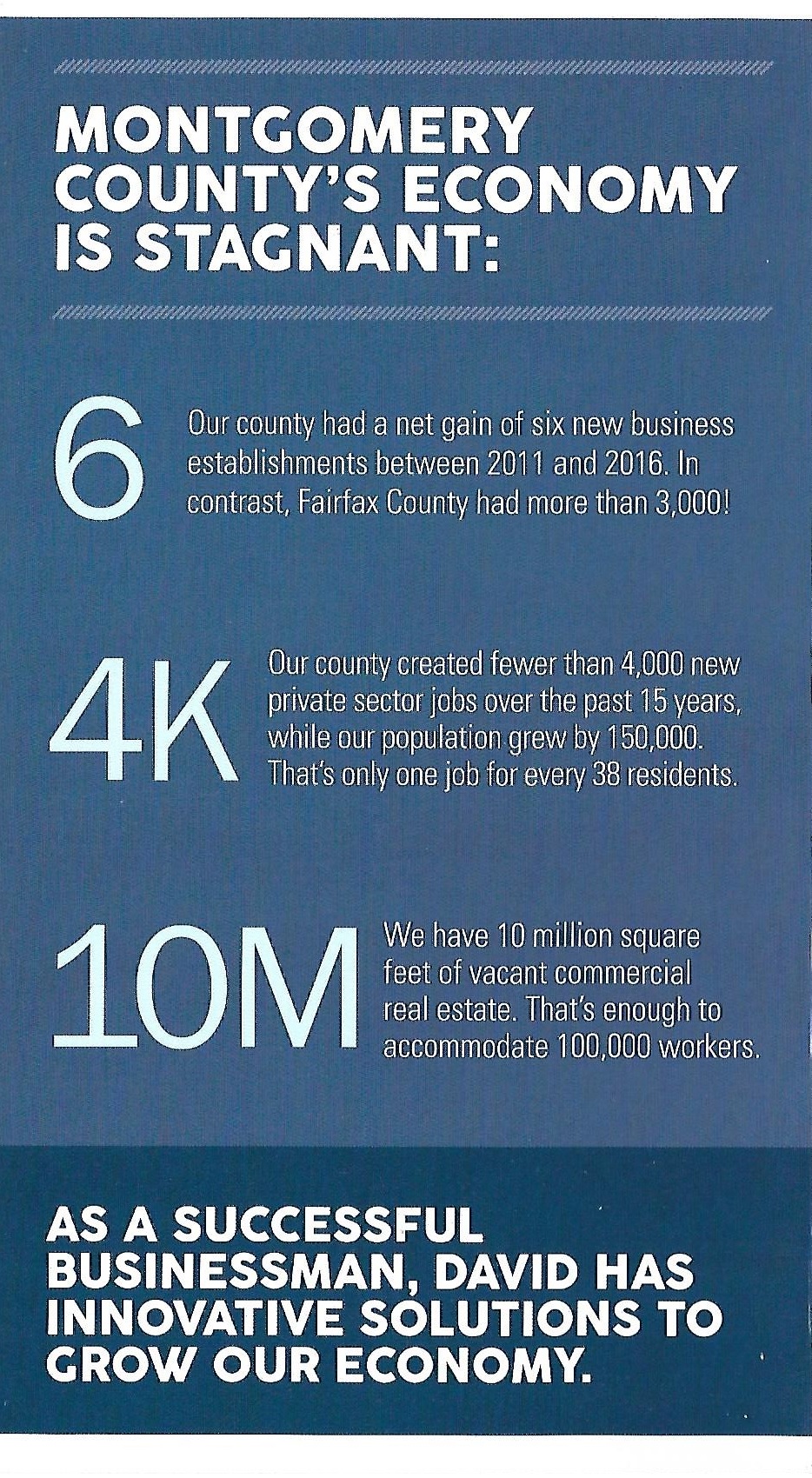

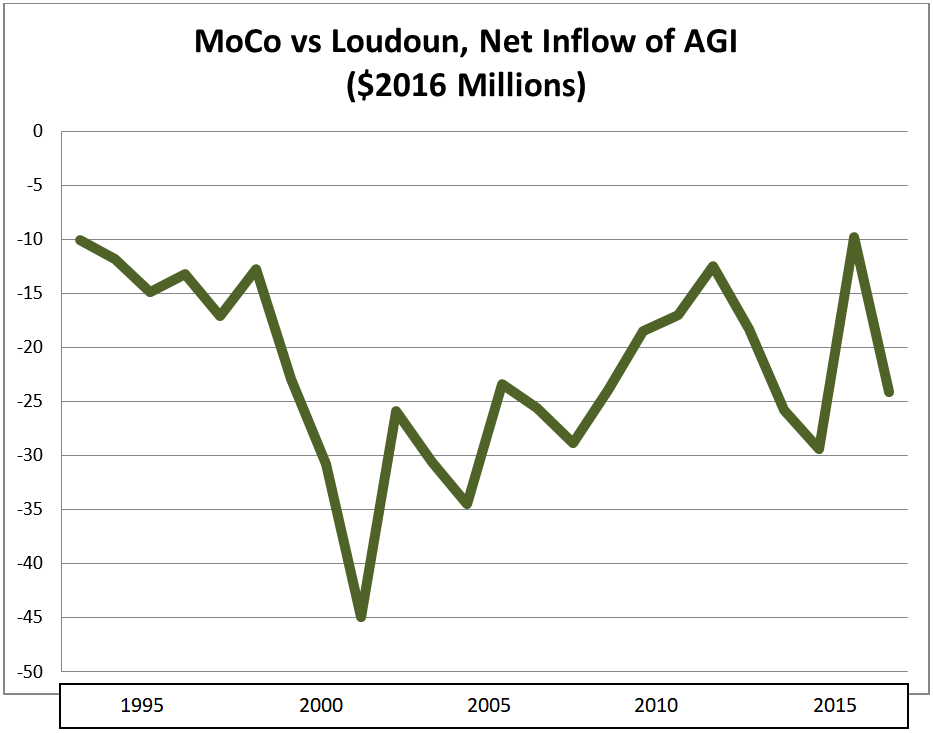

Empower Montgomery (EM) released a report today, displayed at the bottom of this post, arguing that Montgomery County faces strong economic headwinds. In particular, it highlights “a disproportionate, unhealthy reliance on residential tax base” for new revenues and a corresponding lack of growth in commercial business.

And this is where they lost the plot.

Despite having identified the lack of growth in commercial business, and “unimpressive” commercial real estate valuations, as critical challenges for the county, EM’s number one solution is bizarrely geared towards promoting more residential growth.

Specifically, EM’s report expresses alarm that several areas in the county could soon face building moratoria because of the lack of sufficient spaces in public schools to educate more kids. Empower Montgomery regards moratoria as a major business challenge and calls for building more schools to prevent them.

Leaving aside the question of the best places for needed capital investment in the public school system, often in existing schools, the problem facing Montgomery County is not residential development but commercial business. Put another way, we need more businesses that produce goods and services other than more housing.

Though this is the central point of the entire report, EM’s number one solution (literally, it’s numbered “1”) is obliviously to promote more residential housing growth. EM links school construction, rather than improving what’s inside the schools, to better outcomes. Perhaps it’s not accidental that the former but not the latter enables more housing construction.

In a similar vein, EM comes up with concrete ways to fund school construction. But their report is silent on the question of funding operations, which is far more critical to long-term student success and a heavy ongoing cost. Again, one might almost think schools are more about housing development than child development.

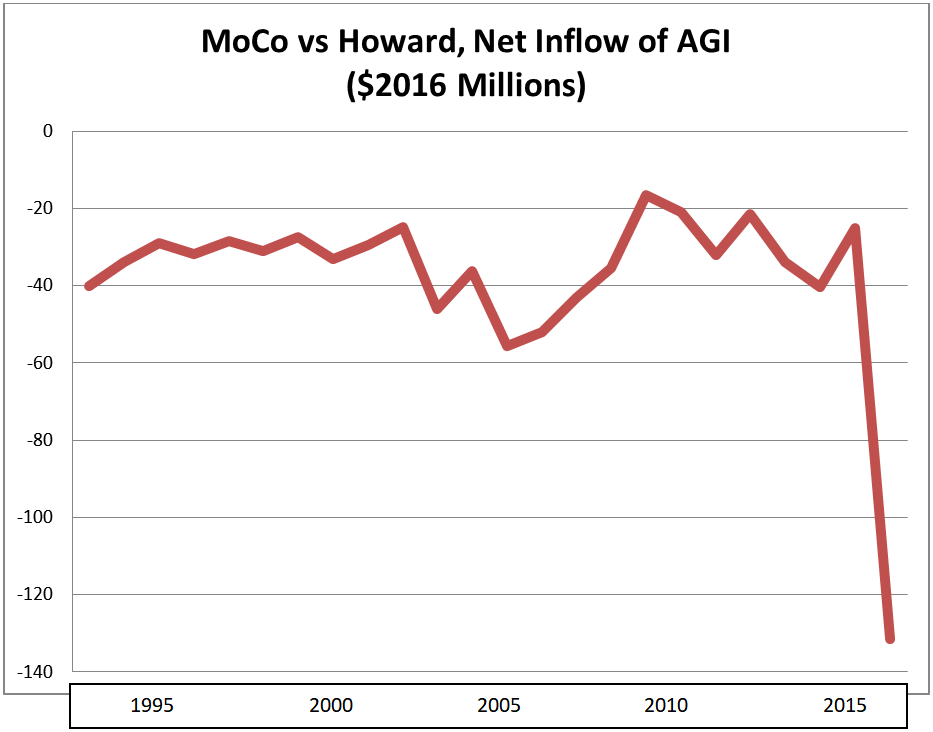

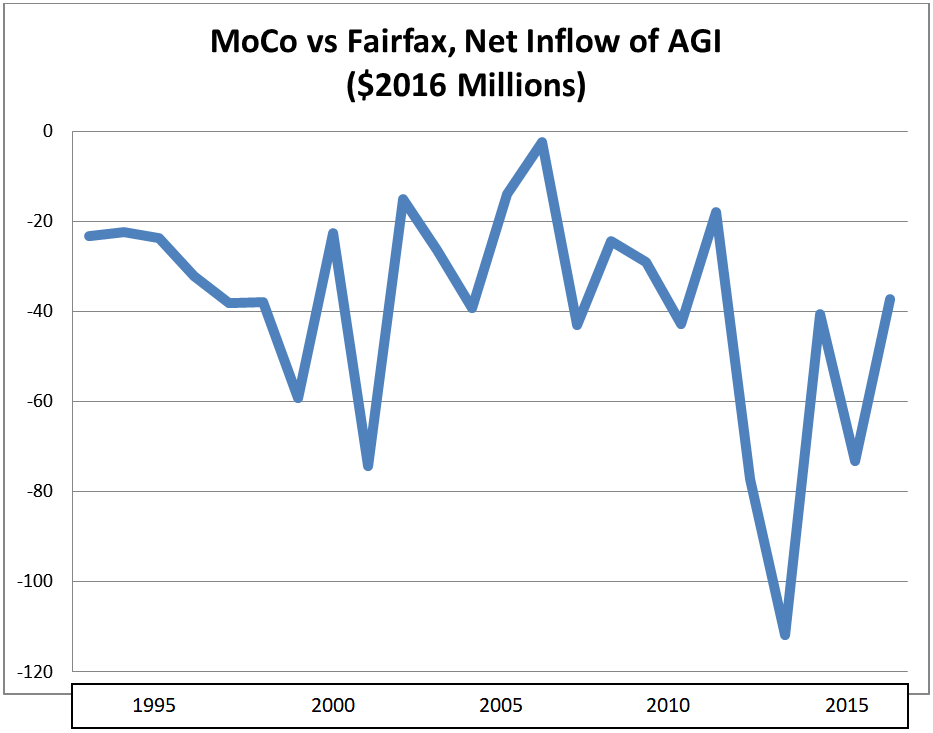

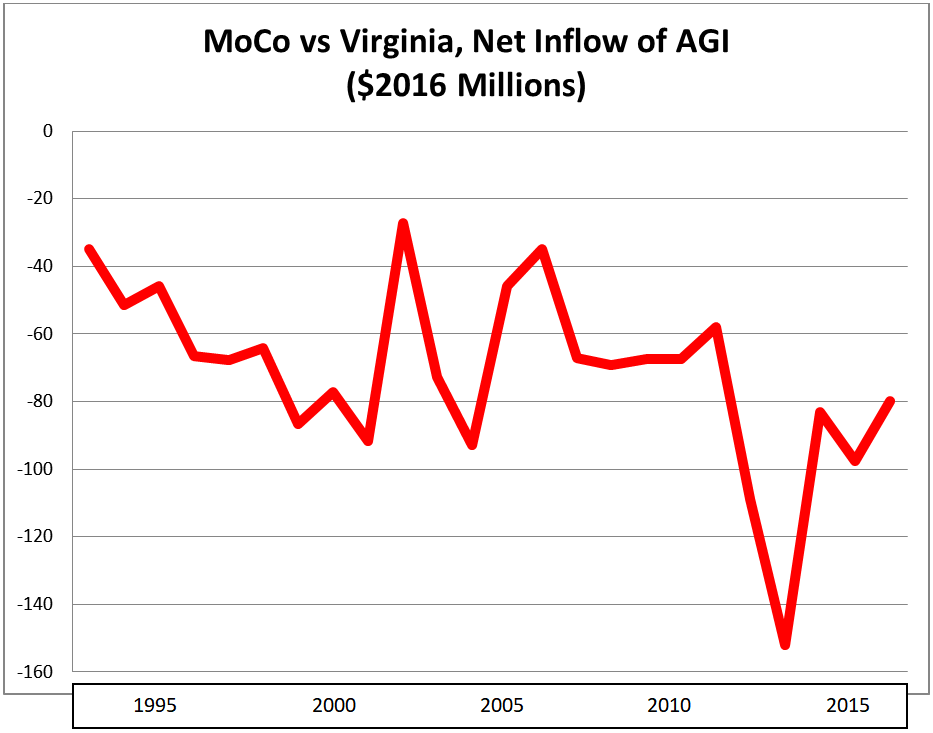

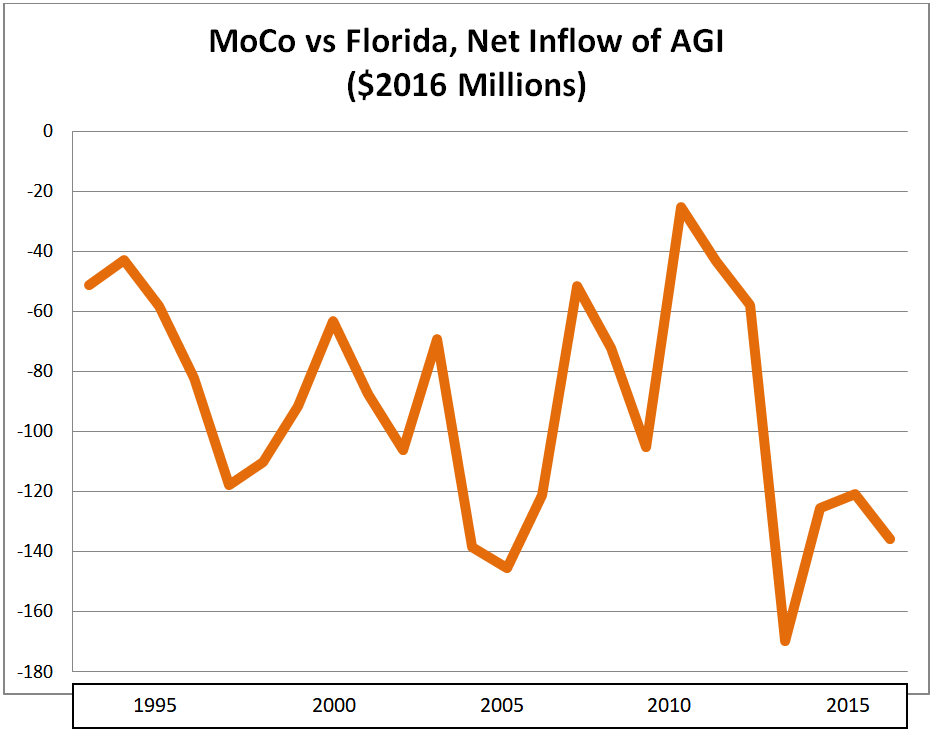

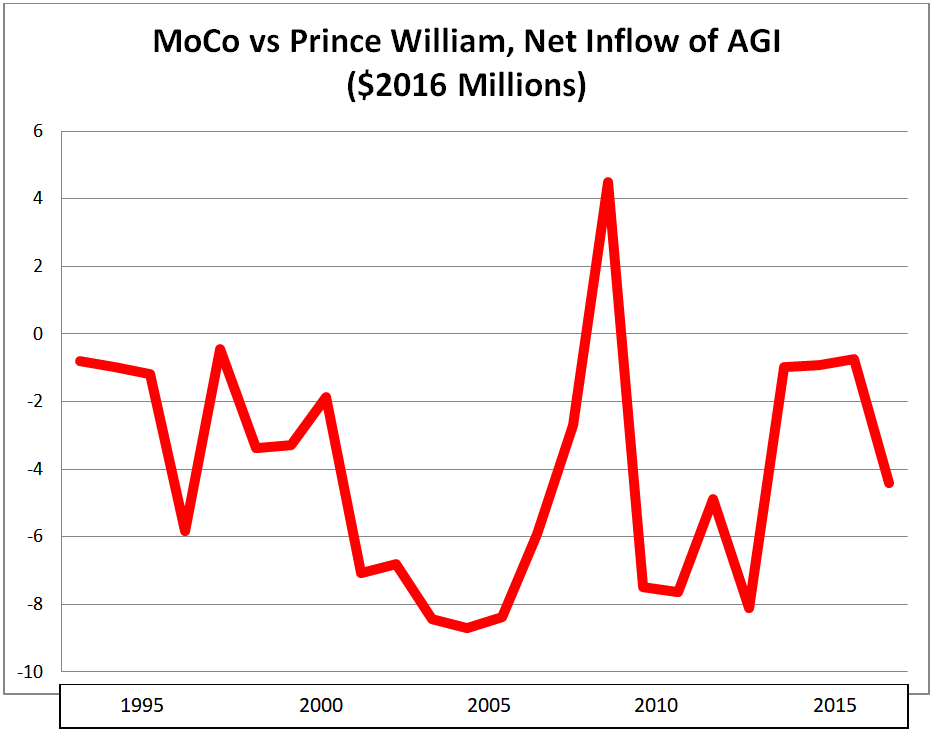

Beyond failing to make the connection between school construction and student performance, EM’s report completely neglects to explain why building more residential housing attracts new commercial business. That may be because the report itself inadvertently shows that it doesn’t. After all, EM’s report reveals that Montgomery’s housing stock and population have grown without attracting needed new business.

The truth about residential development is that it is often unprofitable from the county’s perspective. Once the builders are gone, they leave a new group of residents demanding additional infrastructure and services. While commercial business brings both employment and tax revenues, new residential development is much closer to a break-even proposition.

Even new residents who don’t need special government services—and many will—still require more police and fire protection. More residents mean we need more people at the 911 call center to take just one mundane example.

One set of new residents is especially expensive: children. Education is by far the most expensive service that local government provides. It takes up roughly one-half of the current county budget. Very few families are net contributors to the county budget while they have kids in the public schools. Unless we’re willing to increase classroom sizes, it’s also not easy to achieve economies of scale.

Depending upon who moves into new homes and infrastructure required, and the county school system remains a core asset, residential development can even exacerbate county balance sheet problems. I’m not saying education is not a worthwhile expense. As an educator, I have a decidedly vested interest in promoting it. But it’s not cheap.

In short, focusing on residential development as the solution ignores the critical problem. Even more myopically, it utterly ignores election results not just in Montgomery but also in other parts of the state, such as Anne Arundel, expressing frustration with the lack of infrastructure to support current residents.

Let’s be blunt. For too long, the county has often conflated building and business. We need to spend a lot more time thinking about how to attract and to grow commercial businesses into commercial spaces than building more residential housing. Attracting more business would sure help us afford the new residents for whom there is already ample zoning.

EM is right that expanding the commercial tax base has to be a key part of addressing that problem. As the previous county council under the leadership of Councilmember Nancy Floreen revised the zoning code in a pro-business manner, it would be welcome if the new council would turn its attention to promoting new commercial business.

In contrast, pursuing EM’s approach on development would be a perfect example of trying the same solution again and expecting a different result. Why on earth shoring up residential development is touted as essential when the central problem is a badly anemic commercial business sector remains a mystery.

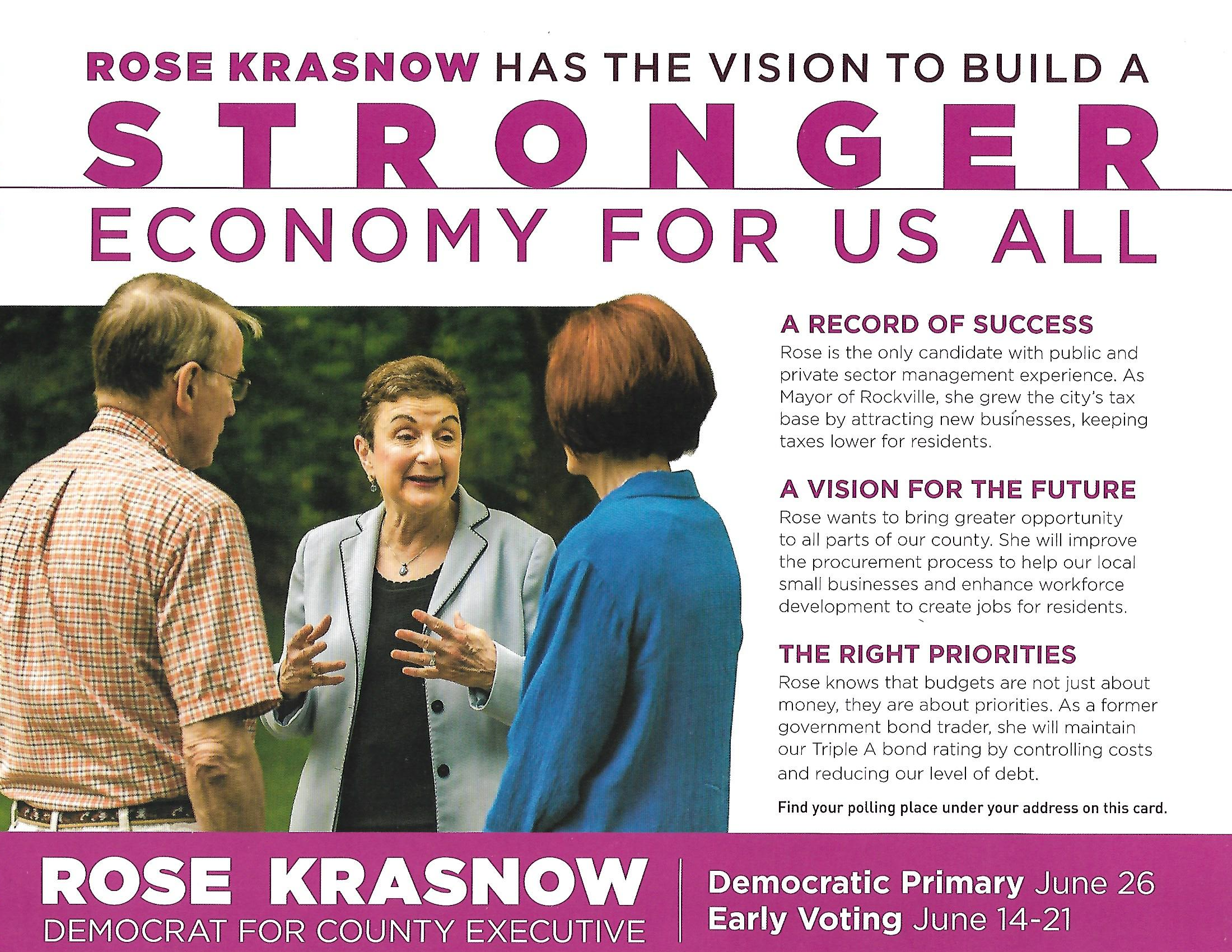

Empower Montgomery is a business group—it supported David Blair for county executive—and it unsurprisingly contains pro-business recommendations. In terms of residential development, their approach represents more of the same, and it’s not going to cut it.

We are not going to solve our problems in attracting new commercial businesses by building more residential homes. At the same time, EM is right that expanding the commercial tax base has to be a key part of addressing that problem. Other ideas in the report may be well worth considering. I’m certainly a fan of privatizing the liquor monopoly.

The previous county council just revised the zoning code in a pro-business manner. It would be welcome if the new council would shift its attention to promoting new commercial business. We have a bunch of new councilmembers who hopefully can bring new perspectives on how to bring new business vitality to the county.

It would also be terrific if the business community would partner with the new executive and council in figuring out ways to both make Montgomery County government more innovative and efficient, and also work far better to attract business. Reforming county government has been a central plank of Marc Elrich’s platform. If business doesn’t take him up on it and keeps making him out to be the boogeyman, they’re missing a real opportunity.

Business needs to play a bigger role in helping move Montgomery County forward. But this report’s focus on residential development as a solution to commercial business problems suggests that the political representation of business may be just as skewed towards the residential developers as the county’s tax base is to residential development.