America in Miniature has very distinct political regions. I’ve divided Maryland into seven here. Republicans eliminated many of the remaining Democratic officeholders in 2014 in three rock-ribbed Republican regions–Western Maryland, Eastern Shore, and Outer Baltimore Bastions. Democrats retain iron grips on the Washington Suburbs and Baltimore City. These areas have very completely different interests and perspective on key issues facing the State.

Among the two remaining regions, Southern Maryland is really divided into two areas moving strongly in opposite directions, which just reinforces the divisions between the other regions. However, the four counties in the Swingy Outer Suburbs constitute the more marginal political territory in Maryland elections. Often up for grabs, Republicans advanced in 2014 through impressive gains in this important region.

Western Maryland

District 1 and 2 are located entirely within Garrett, Allegany, and Washington counties, and both will send entirely Republican delegations to the General Assembly. Their county commissions are also all one-party affairs. Hogan won between 75% and 80% of the vote in these three counties.

Eastern Shore

The Eastern Shore contains nine counties: Cecil, Kent, Queen Anne’s Dorchester, Caroline, Talbot, Somerset, Wicomico, and Worcester. Districts 35A, 36, 37, and 38 are located on the shore (the rest of D35 includes northern Cecil and will be discussed with Harford.) Unsurprisingly, Hogan did well here, taking between 65% and 80% of the vote in the nine Eastern Shore counties.

(Corrections made to this paragraph.) The Shore’s General Assembly delegation is heavily Republican. Majority-black District 37A’s sole delegate is the only Democratic delegate as compared to nine Republicans. Thanks to the political talent of Sen. Jim Mathias, the Democrats also hold one of the Shore’s three Senate seats. Republicans also dominate country government with 34 commission or council seats to just 11 for the Democrats.

Republicans hold all seats on the commissions or councils of Cecil, Queen Anne’s, Caroline, and Talbot Counties. They also form majorities in Wicomico and Worcester Counties. Democrats hang on to majority status by a single seat in Dorchester, Kent, and Somerset Counties–three of the Shore’s smaller counties.

Baltimore City

All six senators and sixteen delegates from the City are Republicans Democrats (Districts 40, 41, 43, 45, and 46 in their entirety as well as District 44A). The Democrats sweep city elections with similar regularity. Hogan won 22% of the vote in the City–not too bad really for a statewide Republican candidate.

Washington Suburbs

Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties are the two other large Democratic bastions. Together they contribute 16 senators and 47 delegates to the Democratic majorities in the General Assembly (Districts 14-27, 39, 47 but 27C is completely outside of Prince George’s). Democrats also easily mop up the seats on both county councils. Hogan received 37% of the vote in Montgomery but only 15% in Prince George’s.

Southern Maryland

The three counties of southern Maryland have been trending in two different directions. While growth, particularly that related to the Navy, has tilted Calvert and St. Mary’s increasingly Republican, growing African-American suburbanization has pushed Charles in the other direction.

Democrats now control the senator and three delegates from Charles (District 28) and hold all county offices. On the other hand, Republicans hold the one senator and four delegates elected entirely from St. Mary’s and Calvert (District 29 and District 27C), as well as completely dominate county offices. Hogan won 69% in Calvert and 73% in St. Mary’s. Though Hogan lost Charles, he showed surprising strength at 47% in a county that has gone for the Democrats by steadily increasing margins.

Swingy Outer Suburbs

Anne Arundel, Baltimore County, Frederick and Howard are key pivots in state elections. All went for Hogan–52% in Howard, 59% in Baltimore County, 64% in Frederick, and 66% in Anne Arundel. All have mixed representation on their county councils with Howard heavily Democratic, Baltimore leaning Democratic, Anne Arundel leaning Republican, and Frederick heavily Republican. Republicans hold county executive seats in Anne Arundel and Howard while Democrats claim Baltimore County and Frederick.

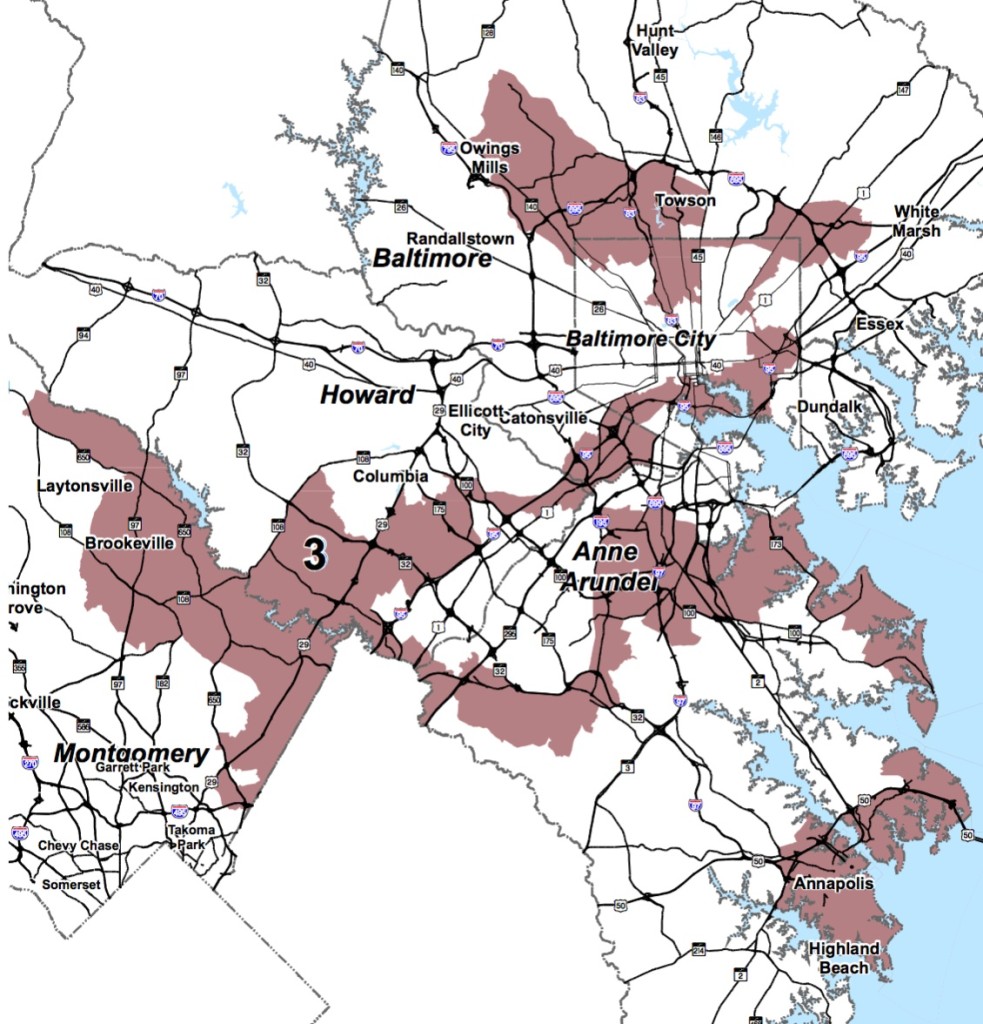

Many of the more competitive elections for the General Assembly occur in these four counties, though there are also several solid legislative districts for each party. (Districts 3-4 in Frederick, Districts 6, 8, 10, 11, 42 and 44B in Baltimore, Districts 9, 12, 13 in Howard, District 30-33 in Anne Arundel.)

While Democrats lead 10-5 in Senate seats, they hold a smaller margin of 15-13 in House seats for these counties. Republicans picked up a several seats that Democrats had hoped to take in this region in 2014. Republicans have to continue to do well in these areas if they hope to make inroads in Maryland. All four counties have been moving towards the Democrats in presidential contests.

Outer Baltimore Bastions

Carroll and Harford Counties are Republican dream lands. Hogan was 82% in Carroll and 77% in Harford. Republicans control all county council seats in both places, as well as the executive in Harford.

Republicans now control all but one General Assembly seat, sending four senators and ten delegates to augment the GOP Caucuses. One Democratic delegate hangs on in District 34A. (District 5 is entirely within Carroll and 34 within Harford. District 7 straddles the Baltimore-Harford line but resembles Harford politically. District 35B is split between Cecil and Harford with 35A in Cecil.)