By Adam Pagnucco.

The untold story of last year’s 9% property tax hike is that it was not merely the product of needed funding for public schools or the adverse consequences of a U.S. Supreme Court decision on income taxes. It was also the product of an innate bias towards more spending built into the County Council’s budget process. That bias created mounting pressure to fund ever-growing spending programs accumulated over many years which contributed to the tax increase. The next generation of county elected officials must reform this process or they too will eventually feel compelled to raise taxes.

All state and local operating budgets must be balanced each year as a matter of law. At the state level, the General Assembly may cut spending items in the Governor’s budget but they generally cannot add to them. (The legislature can and does pass laws mandating spending on certain items in future years.) Several counties with Executives follow the state’s model, as does the City of Baltimore. But the Montgomery County charter grants all final budgetary authority to the County Council, which can do almost anything it wants to the Executive’s recommended budget. It can add, subtract or rearrange spending items subject only to requirements in state law, such as mandatory minimum funding levels for public schools and the college. Other than that, the only constraint on the council’s power is that the budget it passes must be balanced for the fiscal year.

Every March 15, the Executive is required by the charter to send a recommended budget to the council. The council then begins its process for reviewing and changing the budget that lasts roughly two months. The council’s vehicle for altering the Executive’s recommended budget is the reconciliation list (commonly called the rec list), which is a ledger of spending additions and deductions. Each council committee, and the full council itself, can post additions or deductions to the rec list. The last step in the process is figuring out how to finance some portion of the additions since they always exceed the deductions.

In theory, there are two sound places to go to fund additions to the Executive’s budget: new tax revenues or offsetting spending cuts. In practice, the council’s use of these resources is limited. Tax increases are typically proposed by the Executive, who distributes the revenues they generate across spending items in the recommended budget. In such cases, the new revenue is not available for further spending desired by the council unless it alters the Executive’s choices. The council could also cut the Executive’s spending items and use the money for its own items. But the Executive’s spending proposals have constituencies who will squeal if they are diverted or cut. No one likes to be the bad guy at budget time!

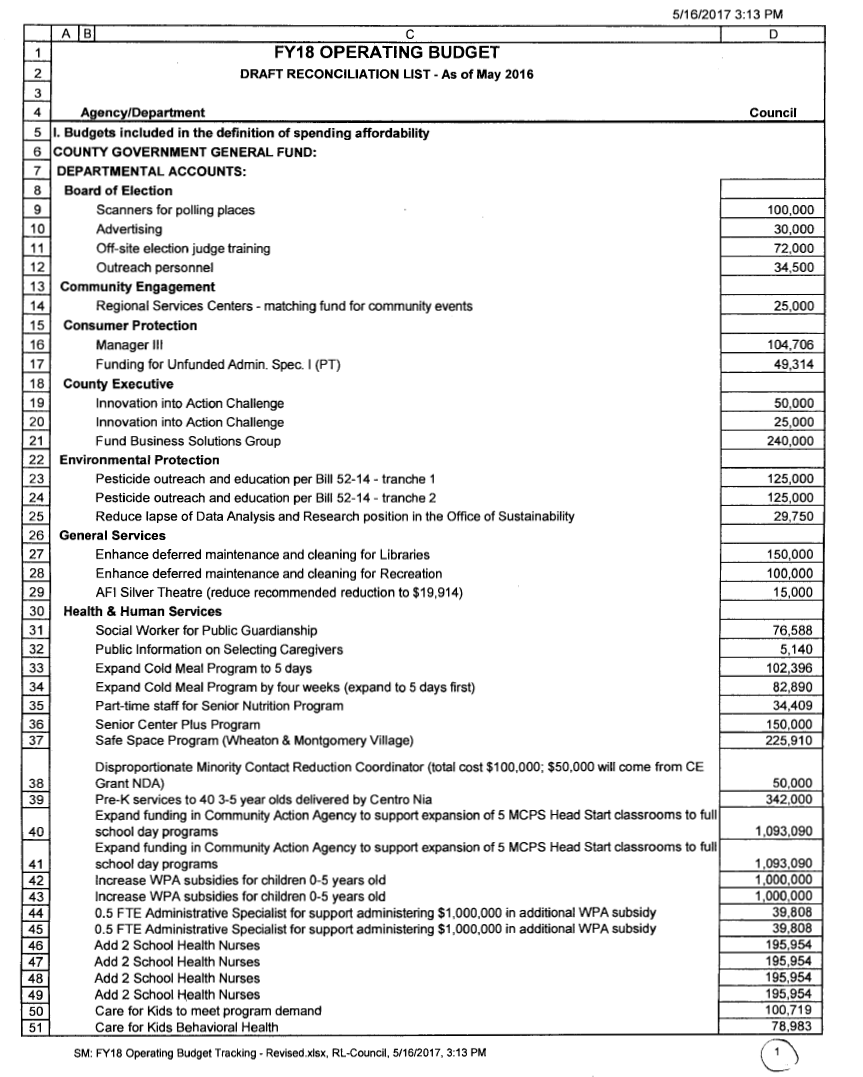

Page one of the council’s final draft reconciliation list for FY18. These are some of the new spending items the council wanted to fund last spring. The challenge was how to pay for them.

If new taxes and spending cuts are insufficient to pay for new spending desired by the council, other funding sources must be identified. In the past, favorite sources for funding included setting aside less reserve money than proposed by the Executive, setting aside less money for retiree health benefits, occasional transfers of cash from the capital budget and other one-time fixes. In FY12, the Executive proposed $10 million for snow removal and the council redirected $4.1 million of that for new spending on the reconciliation list. Snow removal costs must be paid, so if they were to ultimately prove larger than budgeted funds, the council’s action would be tantamount to a backdoor drawdown of the reserve.

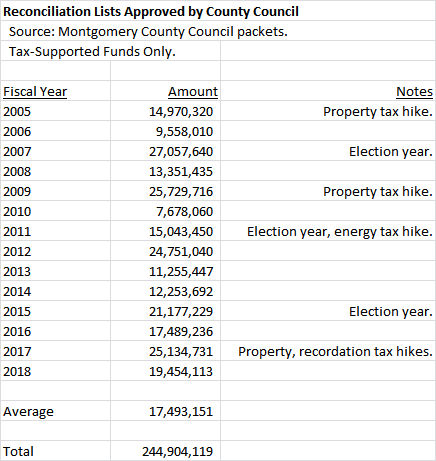

Since FY05, the council has added a combined $245 million to the Executive’s budgets through its reconciliation lists. One does not have to be a certified public accountant to see what the effect of these additions will be over time. Many spending items added by the council are ongoing, such as hires of new employees and expansions of programs expected to continue indefinitely. But some of the funding sources for the new spending are one-time in nature, like capital budget transfers and reserve drawdowns. Repeated use of one-time funding sources for ongoing spending creates enormous long-term pressure on the budget. Eventually, especially when a downturn comes, the new spending must be trimmed or taxes must be raised. Guess which is more likely to occur?

Why does this happen? It’s not because elected officials are stupid. It’s because of the incentives they face. From mid-March through mid-May every year, Council Members are besieged by requests for more spending from the community. Every year, there are three nights of hearings jam-packed with constituents wanting more money for their favored programs. They are followed by dozens of meetings with groups who want even more than that. Aside from occasional admonishments from council administrator Steve Farber and Executive Branch budget officials, there are almost no voices for moderation in the budget process. And here’s the thing: whether it’s hiring social workers, funding more childcare assistance, deploying more police officers in communities that need them, removing more tree stumps or much, much more, almost all the new spending proposals have merit. Given the incredible pressure brought to bear by groups with genuine funding needs, it’s kind of a miracle that the budget gets balanced at all.

All of this creates serious problems for the County Executive. The charter grants the Executive a line item veto over spending items, but this is never used because the council would simply override it. The Executive could abstain from including the council’s new spending in next year’s budget, but again, the council could just put it back in. For the most part, the Executive and his top aides grumble in private and put on a happy face for Wall Street, but they did go public in objecting to a $10 million draw from the reserve two years ago. Instead of fighting the council, the Executive’s staff simply tries to figure out how to retain and pay for the council’s new spending in next year’s budget. And each year, the job gets a little harder without new revenue.

This process is a big reason why the county has had seven major tax hikes in the last sixteen fiscal years.

Next year, a new County Executive and at least four new Council Members will take office. This new generation of officials will have a choice. They can keep the existing budget process and eventually come under pressure for yet another tax hike, as happened last year. Or they can reform it by requiring that new ongoing spending be offset by actual ongoing spending cuts, not one-time measures. Failure to learn this lesson will mean repeating history.

We will conclude with one last lesson from the Giant Tax Hike in Part Three.