By Adam Pagnucco.

After successfully passing a temporary rent stabilization bill in April, Council Member Will Jawando has introduced a permanent rent stabilization bill for many properties within one mile of Metro stations or a half mile from bus rapid transit stations. The bill would exempt certain properties, such as licensed health care facilities, non-profit properties, owner-occupied group houses, religious buildings, transient lodging, dormitories, nursing homes and accessory apartments. It would apply to new buildings after five years of operation as rentals. Buildings not exempted would be allowed to charge annual rent increases up to the county’s (currently) voluntary rent guideline, which was 2.6% in 2020. The guideline is pegged to the rental component of the Washington-Baltimore CPI-U, which is produced by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and has varied between 1.5% and 4.0% over the last decade.

This bill was always going to have a rough ride but now it has a formidable, perhaps even fatal, obstacle – an economic impact statement predicting mayhem to MoCo’s housing market if it passes.

In MoCo, economic impact statements on legislation are prepared by the Office of Legislative Oversight (OLO), a group of merit analysts housed in the legislative branch. OLO has long produced subject matter reports that are often eye-popping reading, but under legislation sponsored by Council Member Andrew Friedson last year, it has taken over the preparation of economic impact statements from the executive branch.

The economic impact statement on Jawando’s bill, reprinted at the end of this column, was prepared by former county council and planning department analyst Jacob Sesker, whose work draws much respect from the council and beyond. It is a lethal indictment of rent stabilization both generally and specifically in MoCo. The statement begins with this blunt declaration:

The Office of Legislative Oversight (OLO) expects Bill 52-20 to have a negative economic impact overall. Residents of rent stabilized units would periodically benefit from lower rent increases. Residents of non-rent stabilized units would likely face increased rent costs. The economic benefit to households is smaller than the economic cost to businesses, in part because the household sector would absorb employment and earnings losses associated with decreased revenue for businesses in the real estate industry. Artificially constrained rents will also have a negative impact on asset values and property tax revenues.

Research indicates that rent stabilization could lead to reduced supply of rental housing and upward pressure on the prices of unregulated units (including owner-occupied units). This reduced supply could occur as a result of condominium conversion or reduced construction activity. Research also indicates that rent stabilization programs often result in disinvestment by owners, including deferred or foregone maintenance. There is evidence that rent stabilization has led to neighborhood deterioration or increased crime in some locations.

The statement’s next three and a half pages contains a literature review summarizing many negative findings of rent control, including higher rents for non-controlled units; poor targeting to people in need as wealthy people secure rent-controlled units; increased conversions of rental units into condos; and maintenance issues for controlled properties. These findings are nothing new – they mirror my own review in 2017, which found that economists have recounted problems with rent control for decades. Even the communist government of Vietnam abandoned it, with one official telling the press, “The Americans couldn’t destroy Hanoi, but we have destroyed our city by very low rents. We realized it was stupid and that we must change policy.”

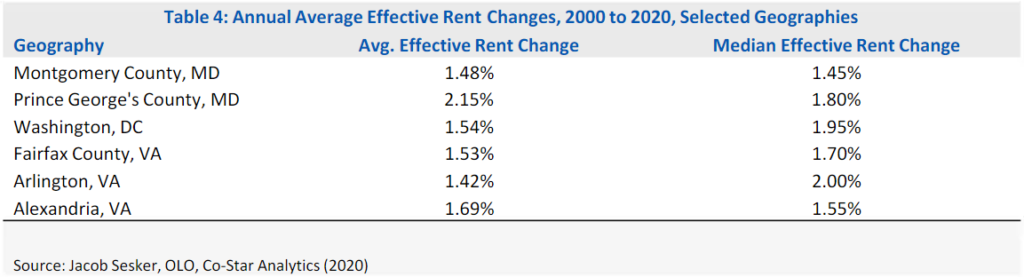

The interesting part of the statement is its research on MoCo’s housing market. Using data from Costar, the statement finds that from 2001 through 2020, rents in MoCo rose by an annual average rate of 1.48%. In properties within 1 mile of rail transit, the average rent increase was 1.28%. Rent increases in MoCo have been among the lowest in the region as shown by the statement’s chart below. If MoCo already has some of the lowest rent increases in the region, what problem is the bill attempting to fix?

While the statement does attempt to model the potential negative economic impacts of rent control on the county’s economy, it omits discussion of MoCo’s two major housing challenges: inadequate rates of construction and slow job growth that deters initiation and financing of housing projects. The District of Columbia has a rent stabilization law and has not seen those problems because it exempts buildings constructed after 1975. (The D.C. Policy Center estimated that just 36% of the District’s rental units were covered by rent stabilization in 2019.) Jawando’s bill applies to new construction after a five-year grace period. Takoma Park’s rent stabilization law applies to new construction and the city is losing rental units. Given the above, what would Jawando’s bill do to housing construction in MoCo?

There will be a lot more to say about this bill from folks with lots of different views on it. That said, since economists overwhelmingly oppose rent control, the advocates have a lot of work to do.

The economic impact statement is reprinted below.