By Adam Pagnucco.

In a June 4 op-ed in the Washington Post and comments reported by WTOP, County Executive Marc Elrich has promised to reform the Montgomery County Police Department (MCPD). According to WTOP, Elrich said MCPD has “an institutional problem” that “starts top down.” He said that he will be submitting a contract to the county council “for reevaluating everything” about MCPD.

If Elrich does intend any serious reforms, he will have to deal with a powerful document that can be invoked in response to them: his own contract with the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) Lodge 35. The FOP’s contract, which Elrich personally signed, gives the union and individual officers substantial authority to restrict the ability of the chief to run the department, keep employee information confidential, block access to personnel records and mandate the destruction of certain personnel and video records. The contract even obligates the county to help the FOP block answers to public information act requests for videos and data. Many of these kinds of provisions are not unique to Montgomery County. But as the executive who signs union contracts as well as a 12-year member and former chair of the county council’s Public Safety Committee, which oversees the police, Elrich is directly responsible for their implementation here.

Here are some of the provisions of Elrich’s 2019-20 contract with the FOP.

Under certain circumstances, the FOP can force the police chief to bargain over new or changed rules or directives.

Article 61 (Directives and Administrative Procedures) contains a set of procedures that constrain the police chief’s ability to implement new or changed rules or directives. When the chief seeks to implement a new rule or directive or change an existing one, he must notify the FOP. “The primary subject of any new, changed, or amended directives or rules covered by the article shall not include matters currently addressed in the collective bargaining agreement, or matters proposed by the County and rejected by the FOP at the most recent term negotiations, or matters, the primary subject of which, were taken to mediation by the FOP at the most recent term negotiations.”

The FOP may then demand to bargain the proposed rule or directive. If the chief does not agree, the matter goes to the county’s Permanent Umpire who decides if the rule or directive must be bargained. This provision limits the ability of the chief to run his department without the consent of an arbitrator. It could certainly be activated to counter any reform proposals opposed by the union.

If employees are arrested, they must disclose it to their supervisor. However, the disclosure “shall be considered confidential and shall only be shared on a need to know basis.”

Article 15 (Hours and Working Conditions) Section Y contains this language on what happens when an employee is arrested.

Employees shall immediately report, or as soon as practical, to their commander/director or bureau chief, any circumstance where the employee is arrested or becomes a defendant in any criminal proceeding that may result in incarceration, receives an incarcerable traffic citation as defined in the Maryland Transportation Article, has their driver’s license/privilege suspended, revoked, refused or canceled that affects their ability to operate a county vehicle, or is notified that they are the subject of a criminal investigation by any law enforcement agency. If the employee is served with a temporary protective order, temporary ex parte order, or other similar temporary order that impacts the employee’s ability to carry a weapon or to perform their assigned police duties or any permanent protective order, permanent ex parte order or other similar permanent order that impacts the employee’s ability to carry a weapon or to perform their assigned police duties, they shall report the matter (as outlined above) directly to their commander/director or bureau chief to be reviewed to determine if the matter impacts the employee’s ability to perform their assigned police duties. The employee shall provide the commander/director or bureau chief with the information (i.e. date/time/location of the alleged offense, case/docket/tracking number) required for the employer to obtain additional information. All information shall be considered confidential and shall only be shared on a need to know basis. It is recognized that all persons are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

In Maryland, criminal records are public documents accessible through the state’s judiciary website. This language prevents police supervisors from disclosing at least some information that is public record.

Management does not have an unfettered right to access personnel records.

Article 51 (Personnel Files) Section B gives an employee and their authorized representative access to the employee’s personnel file. Additionally, the following individuals can access the file only on a “need to know” basis: the employee’s supervisor, an appointing authority or designee, the county’s Human Resources Director or designee, the county attorney or designee, the Chief Administrative Officer or an Assistant Chief Administrative Officer, and members of a Recommendations Committee when an employee has applied for a position vacancy announcement.

“Need to know” is not further defined in the section other than for the county attorney, when it is defined as “when an employee is in litigation against the County, e.g., Merit System Protection Board, Worker’s Compensation, Disability, Retirement, etc.)” and members of a recommendations committee, when it is defined as “limited to performance evaluations, letters of commendation, awards and training documents for bargaining unit members assigned to Recommendations Committee.” Release of personnel records to anyone else is prohibited without the employee’s signed authorization.

Personnel files are destroyed five years after an employee leaves county employment.

Article 51 (Personnel Files) Section E states the following.

- Except as provided below, all records including medical and internal affairs files, pertaining to separated employees shall be destroyed five (5) years after separation, unless the files are the subject of pending litigation. In which case, these files will be destroyed at the conclusion of the litigation.

- The County may maintain records necessary to administer employee benefits programs, including health and retirement, a file containing the employee’s name, address, date of birth, social security number, dates of employment, job titles, union and merit status, salary and like information.

- Except as required by law, no information may be released from any file without the express written permission of the separated employee.

Section H adds these restrictions.

- To the extent not specifically preempted by State law, adverse information concerning an officer’s past performance shall not be admissible in any proceeding unless maintained in strict accordance with this article.

- Except as provided in paragraph 1 of this section, only information properly maintained in personnel files as established by this Article may be used in any other process, proceeding, or action.

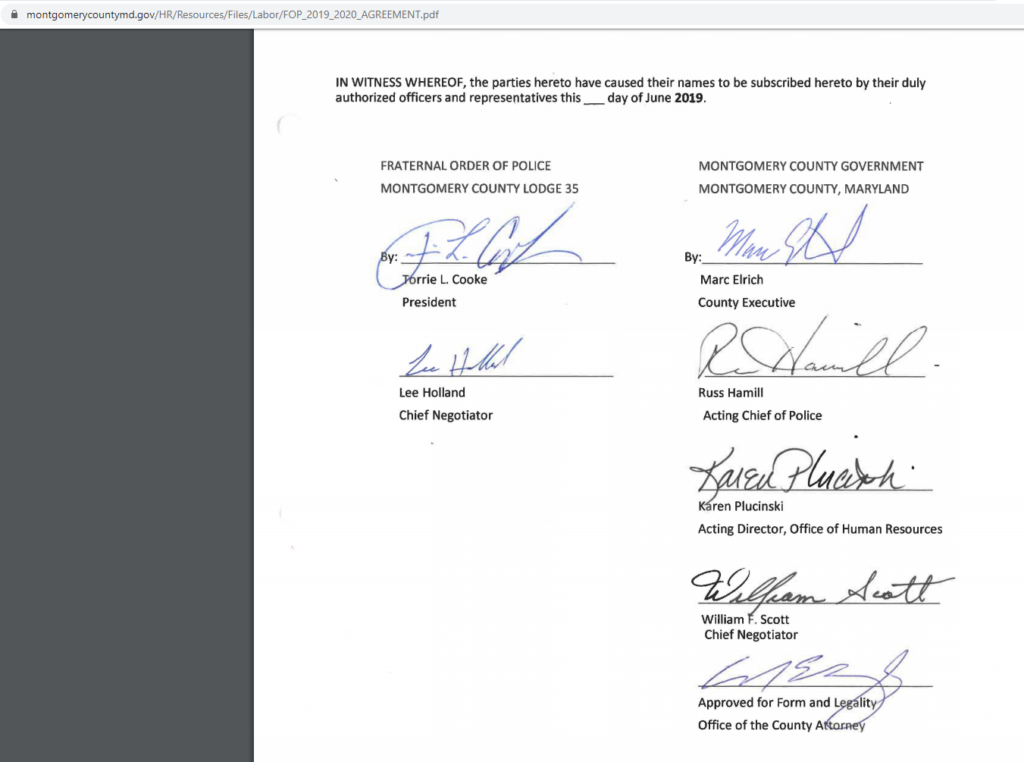

Elrich’s signature on the FOP’s 2019-20 contract.

Mobile Vehicle System (MVS) recordings may not be used for performance evaluations.

Article 66 (Mobile Vehicle Systems) Section C.7 states, “No recording may be used for the purpose of performance evaluations.” Section C.6 states, “All recordings will be destroyed after 210 days, unless the recording is, or may reasonably become, evidence in any proceeding. A recording will be retained if the FOP provides notice to the Department within 210 days of its potential use in a hearing.”

Management may use MVS recordings for disciplinary purposes under certain circumstances including external complaints, pursuit, collision, uses of force, injury or when management has “reasonable basis to suspect that a recording would show an officer engaged in criminal wrongdoing or serious allegations of misconduct in violation of Department rules and regulations applicable to bargaining unit members.”

Body camera recordings “shall not be routinely reviewed for the express purpose of discovering acts of misconduct or instances of poor performance without cause.”

Article 72 (Body Worn Camera System) Section D.2 states:

BWCS recordings shall not be routinely reviewed for the express purpose of discovering acts of misconduct or instances of poor performance without cause. An employee’s supervisor may use BWCS recordings to address performance when cause exists. Any recording used must be reviewed with the subject employee prior to any documentation of performance. Any documented review will be included in the employee’s supervisory file. The employee shall have the opportunity to respond in writing to the document. The response shall be attached to the supervisor’s document. The employee and the employee’s representative shall be provided access to the referenced recording if requested. Performance evaluation shall not be the sole reason for the employer retaining a recording beyond the agreed upon term.

Section F.1 states, “All BWCS recordings will be destroyed after 210 days, unless the Department deems it necessary to retain the recording for a longer period of time.” Section F.2 states, “An employee may elect to save BWCS recordings for longer than 210 days if the recording was used to support a performance evaluation which resulted in a single category being rated as below requirements.”

Police instructors are prohibited from having sex with trainees. However, they cannot be disciplined for it.

Article 15 (Hours and Working Conditions) Section L prohibits instructors and field training officers (FTOs) from having sex with trainees whom they are instructing. If that happens, the instructors and FTOs are separated from the trainee’s class. However, if the instructor or FTO discloses the relationship to management, “managers and supervisors must maintain the disclosure in confidence” and “no disciplinary action or retaliation must occur as a result of the disclosure.” If the relationship is not disclosed but is otherwise discovered, the more senior officer is involuntarily transferred but “violation of this rule will not result in discipline.” Nothing in the contract prohibits the instructor or FTO from proceeding to train other trainees.

The contract obligates the county to help the FOP block answers to certain public information act requests.

The Maryland Public Information Act (MPIA) is mentioned in three different articles of the contract.

Article 65 pertains to Automatic Vehicle Locators (AVLs) and Portable Radio Locators (PRLs), which are described as “systems that allow the Department to identify the location of police vehicles and portable radios that are equipped with GPS tracking capabilities.” Sections D and E address what happens when MPIA requests are made for AVL and PRL records.

Section D. MPIA. The County agrees that it will deny all Maryland Public Information Act (MPIA) requests for stored AVL/PRL data on the movements and location of vehicles assigned to unit members until and unless a point is reached where court decisions establish that AVL/PRL data is public information subject to release under the MPIA. The County will defend its denials of MPIA requests for stored AVL/PRL data in the trial courts, and will continue to defend these denials in trial courts until and unless court decisions establish that AVL/PRL data is not confidential information. The County may, where appropriate, seek appellate review of court decisions ordering the release of AVL/PRL data, but is not required to do so. If the county chooses not to appeal, the employee shall have the right, as allowed by the Court, to continue the appeal at the employee’s own expense.

Section E. Summonses. The County agrees that it will seek court protection from any subpoena or summons seeking stored AVL/PRL data on the movements and location of vehicles assigned to unit members, except for subpoenas issued by a grand jury, or a State or federal prosecutor. The County will seek protection from subpoenas and summonses in the trial courts, until and unless a point is reached where court decisions establish that AVL/PRL data is not confidential information. The County may, where appropriate, seek appellate review of court decisions ordering the release of AVL/PRL data, but the county is not required to do so. If the county chooses not to appeal, the employee shall have the right, as allowed by the court, to continue the appeal at the employee’s own expense.

And so the contract directs the county to block the public’s access to these records in court.

The second article mentioning the MPIA is Article 66, which pertains to Mobile Vehicle Systems (MVS). Section 3.13 states:

All external requests for copies of recordings, including subpoenas and summonses, will be reviewed by the County Attorney’s Office. The County will notify the FOP of all such requests for MVS recordings/data involving unit members and solicit its opinion before determining whether the request will be granted or denied. If the County determines that a request cannot be denied under the MPIA, it will give the FOP an opportunity to file a reverse MPIA action and will not grant the original request until and unless a court orders that the recording/data be disclosed.

This language may violate state law, which allows for a maximum of 30 days to release information disclosable under the MPIA. Courts have been known to take more than 30 days to make findings in lawsuits.

The third article mentioning the MPIA is Article 72, which pertains to Body Worn Camera Systems (BWCS). Section E states:

- Release of BWCS video in absence of a specific request: The County will provide written notice to the FOP prior to the release of any BWCS recording to the public. In the event of an emergency or a bona fide public safety need the County may provide written notice after the release. This does not include release of recordings in connection with litigation, In events where there is no exigency, an employee captured in the recording may object to the use of the recording, in writing, to the Chief of Police (or designee) within two calendar days of receiving the notice of intent to release the recording as to any reason(s) why he or she does not wish the recording to be released. The Chief of Police (or designee) will consider any reason submitted by the employee before proceeding with the release.

- The release of recordings of an employee’s death or injury shall not occur absent compelling law enforcement related reasons to release the recording or in situations where the release of those recordings are required by law.

- The County shall ensure that all external requests for copies of recordings, including subpoenas and summonses, will be reviewed for compliance with applicable standards, including those imposed by law or by provisions of this Agreement. The County will maintain a log of all MPIA requests for BWCS video that it receives. The County will make this log, the underlying MPIA request, and the requested recording, available to the FOP for inspection. If the FOP objects to the release of any portion of the recording, it must promptly notify the County of its objection(s) and its intent to file a “reverse MPIA” action if the County decides to release the requested recording. The County will promptly notify the FOP of any decision to release the requested recording and the date and time of that release, unless the FOP first serves the County with a “reverse MPIA” action it has filed in a court of competent jurisdiction. The parties will make all reasonable efforts to provide each other with expeditious notice under this section given the relatively short time limits in the MPIA and its overall policy of providing the public with prompt access to public records without unnecessary delay.

In summary, the FOP’s contract requires the county to block public access to automatic vehicle locator and portable radio locator data in court and also requires it to facilitate the FOP’s opposing release of motor vehicle and body camera video in court.

If Elrich is serious about reform, he needs to review his own police union contract to see if its provisions are compatible with change. If he doesn’t, the county council will have to step in.